“Home” (fiction)

Image made by the author using Adobe Spark

He uses the rearview mirror to glance at the spot in the backseat where he’d found Josh. No stain. Some people have so little blood in them, he thinks. Since they were kids, that was how it had always been with Josh: almost no blood at all. Only a millionth of a droplet would come out if Josh cut himself shaving. If he cut himself with a knife, then a whole droplet might emerge. Josh’s heart was lazy because it was spoiled. After all, it only had to pump a few droplets of blood a day.

He turns his attention back to the road. Driving through town feels like looking at old pictures of a place you still go to, he thinks. Peering from side to side, he tries to take in as much as he can. He has been imagining this drive since getting here. He drives slowly, creeping along and swerving. He sees the bell tower, the old church lit up, the little Pickle and a Pig restaurant. In only a few days, it has all become so familiar that it feels like home. Some people might say a few days isn’t long enough for a place to feel like home, but he knows better. Why, he’s had some places become home in just a matter of minutes—seconds, even.

He doesn’t notice the cop car in the other lane when he goes to merge. Almost hitting the cruiser, he swerves back into his own lane and presses the brake. He slows to let the cop pass, but for some reason, that crazy guy just slows down, trying to get him to go in front. When that doesn’t work, the cruiser zooms ahead and tears into a frustrated U-turn.

What can he say? He’s a fast actor and a smooth operator. After all, he’d pulled over and rolled down his window before the cop had even had time to put his lights on.

Is the registration in the glove compartment? The insurance? Would Josh have paid them? Josh had been behind on rent, and if he’d been behind on rent, then he had probably been behind on insurance. Josh had been forgetful. Maybe it was because his heart was so lazy.

“Is there a reason you almost sideswiped me?” is the first thing the cop asks him when he finally gets to the window.

A reason for a thing like that? His mind wanders. Once, in middle school, the guidance counselor had asked him why he had his arms folded. “It’s comfortable,” he’d said. “But is there a reason why it’s comfortable?” the guidance counselor had asked. Reasons. Reasons. It’s always “reasons” with people.

He’d love to answer the cop, but he’s kind of busy, so he doesn’t say anything. The cop seems impatient. “You’re sweating profusely,” the cop says. He extends his finger and taps it with the other as he ticks off his observations. “You’re sweating profusely. Then, while sweating, you sideswipe me.”

He didn’t actually sideswipe the car, but pointing that out seems pedantic, even though the difference between hitting a car and not hitting a car isn’t.

********************************

The knock had surprised him that first night, but he wasn’t surprised by who had been at the door. Why, Josh’s friends. He’d invited them in.

After that, they had come most nights. He kept to drinking and smoking, and they kept whatever drugs weren’t drinking or smoking in the bathroom. They would go into the bathroom in small groups, trading out with each other as the night went on. It was a small bathroom, but Josh had it set up nice.

One time, the bathroom door had locked behind Courtney when she went to get her cigarettes in the living room. When she couldn’t get in, she’d knocked on the bathroom door with a hand of painted nails and said, “It’s me.” “It’s me,” she’d said again, louder. The door opened a tenth of an inch, and she flattened herself so that she could get in. It was amazing how she could make herself as thin as a sheet of paper. You had to give it to her, that Courtney, she’s one of a kind.

It was a moving sight, really. He was touched by it. They had told her she could come in, so all she had to say was “it’s me” when she wanted to go in. In the end, she was just being polite anyway because if she wanted to, she probably could have gotten in through the little space between the door and the floor. Recognizing that made him appreciate their camaraderie and her candor even more.

They partied most nights, which was a relief after spending the first few days alone in the apartment with beer from the gas station’s Beer Cave. He’d walked over and bought it with money he’d found in Josh’s bedroom. Every time he spent Josh’s money, he would do something like walk over to the public library to return Josh’s DVDs or throw away all of Josh’s things. It was only fair.

“It’s me,” they’d said at the door that first time. “It’s me,” he’d said.

***********************

He’d searched the parking lot before finding the car, having gone the long way around and entering the apartment complex from the far side in case the maintenance worker had come back. The guy hadn’t wanted to unlock the door in the first place. The rack of keys in Josh’s apartment had itself been shaped like a key, which seemed like a nice touch. You gotta know how to pick ‘em.

Did Josh have a car? None of the keys on the key ring had a logo on them. A yellow number had been stenciled on each of the parking spots. 545, 544, 543.

506. Parking space 506 for apartment 506. You had to love those nice little touches.

He’d seen Josh’s body slumped over in the backseat before he’d even gotten in. He’d fumbled with the keys, trying several before opening the door and then searching its interior with his fingers instead of his eyes. You couldn’t argue with a guy who had fingers for eyes.

After unlocking the door and getting in, he’d noticed that there were no keys inside. Somehow, like a magician, Josh had gotten in, locked himself in without a key, and then died. Maybe Courtney had taught him how to make himself flat, and he had climbed in that way. They can probably all do that out in the Midwest. Maybe it’s like a local tradition.

Come to think of it, he hadn’t had a chance to see much of the town yet. Given that he’d finally tracked down Josh, why not all go for a drive?

What a pair they made. They went all over that town. It took a while, but eventually he found the perfect spot: a covered bridge. It was a walking bridge, not one for cars. Josh would have liked it there. That was what he was thinking as he dragged Josh’s body down to the stream that ran below the bridge.

He decided to head home. It would be a short visit: he would only stay for the sweet beginning and the sweet end. He wouldn’t give the middle enough time to get rotten.

****************

Again, he explained to the cop that he would need a second to find the registration. It was his friend’s car, you see, so he would need a minute to track down everything. Sheesh, sometimes he felt like all he ever did was repeat himself.

The cop left had his lights flashing, which felt like an intrusion, as though the door had been left open during a private discussion.

As he searched, he tapped the glove compartment twice and grunted, so the cop would know he was a hard worker. He wished he had learned Courtney’s trick so he could get out of the car without having to open the door. If he’d practiced hard, he might have been able to sneak through the keyhole by now. He thinks about it and frowns: on second thought, the cop probably would have just gotten him when he came out on the other side.

The cop asks a lot of questions about reasons and keeps repeating some of them. I guess deep down we’re all the same, he thinks. We all repeat ourselves.

Is there a reason why you almost sideswiped me? Is there a reason why your friend’s not here? Is there a reason why you’re here? Where is home, and is there a reason why you’re not there?

Sometimes you can say “it’s me,” and saying it doesn’t help you at all.

“Sandstorm” (fiction)

The room had more people crying at one time than anywhere he had been before. All girls. And him. John kept expecting them to give some indication that they recognized him, but they didn’t.Their red and swollen faces were blank, hideous. Their crying, high pitched and violent, seemed to blend into a single sound as though they had been coached to do it together. He hadn’t been prepared for this when Principal Bogdanski had made the announcement that anyone who had known the kids could go to Room 115.

**********************

It had been hot that morning, and by what John would have guessed to have been 10 a.m., he’d already sweat enough for his oversized Deftones shirt to stick to him. He hated the Deftones now, but he’d liked them last year when he got it. Picking at his shirt made flaky white things float to the ground. A splotch of toothpaste next to the shirt’s image of a screaming cat reminded him of the warped tube of Crest he’d found on Christianson’s bathroom floor that morning. John had brushed with his finger before he and Ian had left.

They’d woken hungry and exhausted, their mouths dry, their adolescent skin broken out from having not washed. Since he’d graduated last year, days at the shop started early for Christianson, so he was gone by the time they’d gotten up. They hadn’t bothered to check who else was still sleeping it off from last night’s party before leaving. There was never anything to eat at Christianson’s place, so they had stopped in Gottimart to swipe breakfast on their way to school.

As they passed through the door to Gottimart, Ian adjusted his Yankees hat by taking hold of it from the back where he had written something in whiteout. This made their entrance feel formal, as though Ian had thought to doff his cap upon entering the building.

Gottimart’s few short rows of items were lit by an old lamp plugged into the wall next to the cash register. The rest of the store was dark. Bob, the owner, used it for storage. Things were piled around: a ladder, old cigarette advertisements, stacks of shipping containers for soda bottles, a flat tire. Stopping at the counter, John put his hand on one of the store’s three bottles of oil. The plastic was hot. The bottle felt like it would cave in if he pressed too hard.

“I just threw up,” Nick Gulatti, who everyone called John Gotti, said from behind the counter. Gotti, the reason everyone called it Gottimart even though he only worked there, had graduated last year with Christianson. An odd guy, he didn’t come around much; his nickname came more from similarities in name than temperament with the mafia don, though he did have the bulging stomach of a Mafioso. He looked like a mechanic. Once John found Gotti’s entry in Christianson’s yearbook. The paragraph below his picture, where everyone else had friends’ initials and allusions to inside jokes, was one sentence: “My favorite Person: Whoever Gives Me My Paycheck.”

“You threw up? Just now?” Ian said with what John thought was exaggerated incredulity.

“Out there,” Gotti said, gesturing with his head toward the staff door behind him. He stood a few feet back from the counter with its ancient cash register and lamp. It made him seem hesitant to be there.

They looked to where he had pointed, but no vomit was visible. “Everywhere,” Gotti said as if saying that it had happened even if they couldn’t see it.

“So, this is just something you do?” Ian said, looking at the racks of candy. John followed his gaze. Not much to choose from. By the time he got to school he would be able to steal lunch from the cafeteria anyway.

Gotti looked at him like he was crazy. “It’s because of what I heard.”

“What’d you hear?” Ian asked as he stepped toward the counter and swiped some Skittles.

Gotti got a funny look on his face.

***************

They traded the bag of Skittles back and forth as they walked. Gotti wouldn’t say what he’d heard or why he’d vomited, which John attributed to him being histrionically loyal to someone who’d asked him to keep quiet about something no one cared about. People with no friends made a big deal about things like that.

The walk to school was a couple of miles. As they went, John picked out the places where he had partied. Partying had sealed off everything behind it. Getting drunk spoke to him as a person. The absurdity of being drunk matched the absurdity of how everything else felt.

The heat made it feel like the school year was about to end, but they still had a month to go. He’d probably have Ms. Morin’s class when he got to school. She’d said something weird the other day. Seeming bored while waiting for the class to line up, she’d asked what Ian’s plans were now that he was going to graduate. “Waste of a brain,” she’d said when he told her Ian wanted to go into the army. “Waste of a brain,” she’d repeated, but before he could ask her what she meant, she’d gotten distracted and started yelling at some kid in the hall.

Waste of a brain.

“Everyone is saying you got a ‘A’ on some big test, or something,” he said.

“Test?” Ian said and then burped. “Oh, the SAT. Don’t worry about that, John, you’ll get something sort of high. It’s real simple: answer what you know, don’t answer what you don’t,” Ian said.

“Nothing to it. Nothing to anything.”

************

Ordinarily, Room 115 must have been a teachers’ lounge. A sink was in back with a green-streaked bottle of dish soap next to it. In the center of the room, smaller rectangular tables had been arranged to make one big rectangle that they all sat around. The teachers must have panicked trying to figure out what to do with so many crying kids.

He stared at the floor. At first, to have something to do, he’d rubbed Krystal’s shoulder, who’d ended up sitting next to him, but he’d stopped after she gave no sign that she knew he was there, which made it seem awkward and almost sexually indecent to keep touching her.

His hands felt sweaty and swollen. He moved his fingers around in his lap before then switching to tugging his hair, which was already thinning. It was greasy, and the top felt matted down. When that started to hurt, he put his hands back in his lap again, before making the change to pulling on the uneven patches of his facial hair. The hair on his chin had grown in nicely, but his sideburns were still just a few wiry black hairs. He could kind of taste the Skittles from Gottimart that he’d had for breakfast. He hadn’t ended up having time to go to the cafeteria and was hungry.

He wondered what Ian was doing up at the high school. He’d probably gotten a ride with Wayne, who could buy beer because he looked old. A few nights before, Wayne had thrown up in Christianson’s room and then used an empty thirty-pack box to catch the vomit. Trying to help, someone had brought him water that he’d poured all over his face, which got the thirty-pack box wet and made it start to leak. Christianson told him to go outside, but Wayne kept giving him the finger and saying, “Don’t dictate terms to me.”

Don’t dictate terms to me. John smiled.

“So, who did you know?” Mrs. Lowry asked, interrupting him. He didn’t know Mrs. Lowry. Bogdanski had probably asked her to watch the kids because she was the guidance counselor. He looked at her and then at the ground. He thought about his answer for a long time. He could have said any of them.

“Dave,” he said finally.

“Oh! But Dave’s okay,” she exclaimed.

He shrugged and gave what felt like a watery smile. “I guess I….” He looked down. He wished he hadn’t come. Somehow it had seemed like this would be better than going to science.

Mrs. Lowry turned from him. This helped because not having her watch made it easier for him to get up from the table.

**************

He ended up at the payphone by the front office. The hall felt quiet and peaceful. It seemed insane now that he had put himself through the experience of sitting in that room. A secretary laughed and it sounded like someone was using a photocopy machine. Through the window, he could see a few cars driving down Main Street.

Dave answered the phone after the first ring. It was crazy to think that amidst all of this he was just sitting at home.

The conversation was short. Dave asked if people seemed upset and if anyone had asked about him. He asked if any girls had seemed upset. He suggested they meet at the bridge near the school. Dave said Ian was already on his way down from the high school and if John waited outside, they could walk to the bridge together.

He left the payphone and walked toward the exit on the other side of the building. Justin, a kid from science, came out of the bathroom when John passed it. John nodded. Justin smirked when he saw the direction John was walking and gave him a knowing look. John kept his face flat.

He exited through the door by the music room. Inside he heard Mrs. Root saying that she didn’t expect them to get up and dance naked, just sing. That was always her line: you don’t have to dance around naked, just sing. Sometimes in music when she said that, he would say, “No one wants to see youdance naked” under his breath and everyone would laugh. The door next to her room opened to Tuttle Road, which was the one Ian would take coming from the high school. He could hide in the bushes until Ian came.

But, then, he didn’t wait in the bushes. He flung open the door and continued down Tuttle alone before taking a left onto Main Street.

Walking, he thought of a book he’d read in school a few years ago, maybe fourth or fifth grade, about a kid who’d made himself photosynthetic doing his science homework. Being outside reminded him of the part when the kid described the feeling of first going into the sun and realizing he was being nourished by it.

He was the first one to get to the bridge. He dragged his hand along its thick cement edge. He peered over the side. Someone had put their cigarette out in a pool of spit on the ledge and his Deftones shirt got in it when he leaned over the side to get a better look.

Below the bridge, a thin black snake sunned itself on a chunk of brick that jutted up out of the water. He used to go down there with his little kid friends and wade through the stream to play; more recently he would go down there with the guys to smoke.

He watched the snake. Reaching down, he picked up a handful of the soft, fine sand that was on the sides of the bridge. Other than its odd golden color, it kind of reminded him of the sand they put in ashtrays at the mall. He wondered how it had gotten there.

He caressed it. Soft. He held his hand out over the side of the bridge and opened it. Sand rained down on the snake, which lazily slithered off the brick and into the water. It darted left and then right before swimming downstream.

The sand left a yellow coating on his hand that made him think of how gold looks in cartoons. It sparkled. He reached down for another handful, but with the snake now gone he instead threw it in the air. He tossed another handful a little higher. A mild wind scattered it as it fell. He tossed a little more, and then more, first with one hand and then with both. The wind picked up. Its force was strong, and it blew the sand back on him as he threw it. Sand hit his face and got in his eyes.

He threw more, higher, and pictured waves of it coating his body and getting into his mouth. He kept going. His mouth felt full and started to overflow with sand. It got so packed that the sand hit against it before falling to the ground, where it started to pile up and cover his shoes. As he kept tossing it up, it piled higher and higher. He gagged, choked. Trying to keep pace, he inhaled lungfuls of it, devouring it as if each lung were a separate stomach with its own mouth.

Unable to breathe, he made circles with his arms as he tossed more and more in the air. It whipped around him, burying everything: the bridge, 115, Mrs. Lowry, Gottimart, the whole town. The accident got wrapped up in it, too, and of course so did he.

He kept trying to flail his arms long after he couldn’t move them anymore.

Why I Left Academia

The author looking for a suitable place to self-immolate

I always think of my first car accident in China when someone asks me about leaving academia. A few weeks before the accident, I’d been a PhD student on a leafy New England campus when my coworker, Ellen, and I found were in a taxi hit by another taxi. Ellen was from the HR Department, which was a one-person department in which Ellen did work she hadn’t been hired to do.

I hadn’t been in China for long by that point, but I’d already figured out that I’d been tricked into working for a high-class, high-tech plagiarism firm. Ellen had taken pity on me and gone rogue in helping me to get out of my contract while maintaining my visa. The process wasn’t simple—streamlined bureaucracy doesn’t rank with Daoism, calligraphy, and education as among China’s many cultural riches.

The clock was ticking, and we were hustling. As I remember, we were rushing to submit an important piece of paperwork to some office. The accident wasn’t serious, but that taxi wasn’t going anywhere, and the driver was freaking out. Rushing against the deadline, Ellen and I played a game of Frogger with the oncoming traffic before climbing through a hole in a fence on the side of the freeway. Stumbling down the embankment, we found ourselves on a weird side street in a residential neighborhood neither of us knew. We were down to the wire, and things looked bleak until, out of the blue, a slow-moving taxi happened by that we were able to flag down.

Ellen was irritated as we got into the back. “I can’t believe this. A day from hell,” she said, arching an eyebrow and glancing at her phone to check her messages. “I’m so sorry.”

“I think this is one of the best days of my life,” I blurted out without thinking.

“What?” she said, seeming perplexed and maybe a little annoyed.

The rest of the day comes to me as a montage of questionable authenticity. I remember the person we were supposed to meet laughing as we tumbled into the room to submit the required form only minutes before the office closed. I remember eating dinner at my favorite noodle place up the street, and I remember sitting on my balcony that night as I tried to escape the humid Shenzhen air.

That probably is what I did that night because that’s what I usually did, but I don’t really remember. What I do remember is being surprised by Ellen’s irritation and thinking that I couldn’t remember a time I’d felt that alive in years.

***

It’s a true story, and it’s true as far as it goes. But this isn’t my shot at a third-rate version of expat Kerouac. Moving to China was the first thing I did after I dropped out of my PhD program. It was an exhilarating time, but of course there was another side to things. Leaving academia was one of the hardest decisions of my life, and after leaving, I grieved like I’d lost a loved one. I remember wincing when I broke the news to my former colleague, Reid, in Café Algiers.

I loved and love academia as much as anyone I’ve ever met (which is not to say I’m as good at it as everyone I’ve ever met). I still read academic sources both for fun and for my professional life as an editor. More than once, I’ve been called an academic machine.

So, why did I leave? There are a lot of answers to that question. There are the more routine ones. Often when the topic comes up, people mention important practical advice. Examples are easy enough to come by: choose a program based on research fit, choose a program with multiple potential advisors, be ready for an extremely harsh job market, etc.

All of that is good advice. Some of it I took, and some of it I didn’t. There’s no question that poor research fit, limited career prospects, and my own thirty-something age were starting to catch up with me by the time I finally got around to leaving. At the time, I was already thinking about going into writing, editing, or publishing, and the fact that literally every person I talked to in those industries recommended I leave my program to get hands-on experience certainly made it easier for me to go. For once in my life, the thing I wanted to do was also the prudent thing to do.

However, the deeper answer for why left I has a lot to do with my willingness to take responsibility for myself. I’d let too much go for too long, and that bill came due. In hindsight, I can see how clearly many of my choices in my teens and twenties were motivated by fear and insecurity. My compulsive attempt to distinguish myself from my mal-intentioned, lumpenproletariat father combined with the feeling that I was behind in life to foster an obsessive perfectionism that at times bordered on self-abuse. That outlook, particularly when united with a moral code that was as quirky as it was rigid, wasn’t a recipe for lucidity regarding major life decisions.

Other troubling dynamics took hold. I was a first-gen college student from a milieu in which college was a fairly unusual path. Amongst my family and friends, no one seemed to know quite what to do with me until we settled on something of a hometown hero role, but that jerry-rigged, pariah-parvenu fix wasn’t sturdy enough to last.

Ultimately, however, the core issue was my own self-infantilizing. In bad faith, I’d convinced myself that outsourcing my decision-making regarding basic life choices would free me up to focus on weightier matters. I turned those decisions over to other people and common-sense solutions. I guess I saw this as the rough equivalent of other strategies I’d adopted to free up cognitive bandwidth, such as eating the same lunch every day to save time (a tossed green salad with raw tofu, a piece of fruit, and a peanut butter granola bar).

I don’t want to turn this into third-rate existentialism any more than third-rate Kerouac, but I suspect at least part of what was behind all of that was an attempt to avoid taking responsibility for having to make major life choices and deal with the messy complexities of life. Surprising perhaps no one but myself, this life strategy mirrored the one my father had employed on a very different register to disastrous and disreputable results. Abdicating responsibility for one’s life is a potent narcotic, and I still have to watch my impulses in that direction.

To bring it back to the PhD, the result was I woke up one day with no real sense of what I wanted out of the degree—or, even more fundamentally, what I wanted out of life. I was riddled with anxiety about my capacity to make decisions. What I experienced as resentment of everyone, and everything, was ultimately a reflection of the resentment I felt for myself after having turned over my life to be lived by others.

My response was to burn down everything I’d built, including a ten-year romantic relationship, and move to the other side of the globe. This forced me to find my own solutions for car accidents, visa challenges, and whatever it was I was going to do with myself. It made life seem impossible in the day-to-day, yet ever easier in the broad scheme of things.

***

Should I have finished it at the time? The answer depends on how far back we go in the thought experiment. If we take our time machine back to the day I chose to leave, then I suppose I might as well have finished. I don’t know how big of a difference it would have made in my life, but I had enough material on Dewey kicking around that I probably could have put together an unremarkable but satisfactory dissertation without terrible strain.

If we go back before that, then I’m not so sure. Hindsight is 20-20, but I certainly could have spent that time in ways that would have made my life a lot easier now. Then again, past a certain point, the question becomes so counterfactual that who’s to say what path I would have found myself on, and there’s no guarantee I wouldn’t have continued fouling things up for myself if I’d continued trying to make that path work.

Besides, I was spoiled, with a quite generous funding package from the university. Little of what I did during that round of grad school had anything to do with building an academic career, but I learned a great deal in a number of areas and left with not much more than my pride damaged. A lot of the skills and bodies of knowledge I picked up are central to my life now, and I salivate thinking about the resources and opportunities that I casually took for granted in the university setting. In the end, I guess I got out of it what I needed, and I have a certain fondness for the experience despite the frustration and bitterness I felt at the time. If I’d had the foresight to know I’d feel this way, I probably could have taken even more from it with less pain.

Would I go back now? There are days I miss it, and there are days I don’t, but that train has left the station. When I left, I’d told myself all sorts of things—I’d go back, I’d transfer programs, I’d switch fields. On some level, I think I knew that was the end, and as is often the case in life, after you’ve moved on, you’ve moved on. The currents are too strong.

***

So, we find ourselves back on that highway with Ellen. Every now and then I hear from her. The last I knew she was living in Vietnam and working as a translator. Once she’d jokingly asked if I still thought that was one of the best days of my life.

“I really don’t know, Ellen, but it was the best of something,” I’d said.

Spit and Style

The only time I spit these days might be when I’m brushing my teeth. I hadn’t thought of that until the other day when I saw someone spitting on the ground in a restaurant. I guess spitting isn’t much a part of my life anymore, but when I was a teenager, we all spit all the time. It’s true we spit beautifully — we had a certain defiant style down pat — and I wonder about its execution and purpose.

Of course, there are different ways to spit just as there are different ways to do any physical thing. Still, it strikes me that its spectrum of meaning is slightly more restricted than that of some other acts. I think part of this has to do with the fact that spitting is more voluntary than something like walking, for example. Many of us walk to get to where we’re going, though we rarely need to spit to do anything.

How one walks can communicate how one feels about others, as in the case of an angry stride or seductive saunter. It can communicate how one feels internally or about oneself, as in the case of a contemplative stroll or anxious plod. The place one chooses to walk can add another layer of meaning, as in the case of a march on the capitol.

I’m not convinced spitting is quite so versatile when it comes to style. This isn’t to say spitting can’t be done in different ways or to communicate different messages. The clinical spit done at the dentist’s office is certainly different from the panicked spit triggered by eating something soiled. Still, in many cultures, spitting is seen as unhygienic and disrespectful. This varies, of course, and I’ve been in settings where spitting was seen as more neutral — akin to a sneeze, I guess. There’s not much room for style when it comes to sneezing; it’s too reflexive and monochromatic. It is not particularly amenable to style, though there’s some wiggle room there. I’m not sure if cultural tolerance of spitting gives it more or less latitude in terms of style.

At least in Western settings, part of what gives spitting its strong but relatively narrow band of meaning is that it’s frowned on. This makes spitting an excellent choice for those looking to be disrespectful. The most violent case would of course be the symbolic and literal pollution of spitting on a person.

The punk rock movement has a long history of spitting — both on things and on people. In the case of punk, given that the culture is premised on being offensive, the choice to join in on the spitting is a way of respecting the culture by disrespecting everything else. I suspect this was more revolutionary in the 1970s. At this point, it’s quite stereotyped and ritualized.

I remember seeing the band Kill in Your Idols in the 1990s and the singer requesting that the audience stop spitting on him. “Do something new — figure out your own thing,” he’d exhorted the audience. “Maybe try spitting in your hand and rubbing it on your face.” A few concertgoers willingly or unwillingly missed the irony and took his advice. As a viewer, I felt that in terms of style, what that strategy gained in innovation it lacked in zeal: dousing yourself in your own spit somehow just isn’t the same as dousing other people or things in it.

As skateboarders in the ’90s, we all spit constantly. This might have been a vestige of the punk rock influence on skateboarding culture, though the cultural antecedents don’t need to be that direct. If anything is egalitarian, it’s spitting. It nicely complemented skateboarding’s outlaw aesthetic. Still, I think many of us wished we would spit less. Falling on concrete was painful and annoying enough without having to avoid pools of spit or have insult added to injury when unsuccessfully avoiding those pools after bumbling a tre flip.

One of my weirdest and creepiest memories of spitting comes from those skateboard days, when a quasi-homeless guy with vaguely pedophilic vibes who always insisted on being called “doctor” attempted to negotiate with a group of us to allow him to video tape us spitting. We rejected the offer, as appealing as it was. Afterwards, I’d spit as I was walking away, which he then scraped up with a folded business card he’d had in the pocket of his soiled shirt. He delicately folded the card before returning it to his pocket. I suppose spitting had a very different meaning for him, though I’d prefer not to give a ton of thought to what that was.

Style aside, one obvious physical explanation for why we spit would have been chewing tobacco, but I don’t remember that being particularly popular when I was growing up. Smoking was, though, and that seemed to correlate with spitting. I’m not sure if that was because we were always spitting and would have done it anyway or because smoking encourages spitting. I do remember the sound my friend Ian’s cigarette made when he put it out in a pool of his own spit, though I suspect the gesture was more utilitarian than symbolic in intent.

As with Ian and his cigarette, maybe we spit just to spit. At the time, I doubt any of us gave thought to what it meant. Still, the stylized and exaggerated manner of our spitting would make it seem more than just a habit. It was often as auditory as visual, and the conspicuous turn of the head and force that accompanied it made clear that we were spitting. I’m convinced you could tease out a subconscious cultural imperative to the performance. We spit because it felt good, sure, but we also spit because it said something about how we saw the world. The message might not have been subtle, but the execution had remarkable panache.

Unlike spitting, I never really cursed much. But even now I have to admit that it does feel good as a release and to punctuate a point. Similarly, maybe I should take a page from my youth and reincorporate spitting into my communicative repertoire. It’s not the most versatile gesture, but it can have a certain blunt flair when done well, and I’ve had enough practice that I could probably still pull it off with finesse.

*Spit*

Mental 📸: Lina Ferreira, Hofstadter, Dark, Karaoke Paradise

Hi! A picture inside my head on this Memorial Day:

📚 “CID-LAX-BOG” by Lina Ferreira

In picking through Phillip Lopate’s The Contemporary American Essay (2021), Lina Ferreira’s “CID-LAX-BOG” caught my eye because of the Colombian connection. It’s very powerful. Lines like the following about a trip to donate blood hit like a blackjack to the nape of the neck:

And as a thin thread of blood drips down my forearm, I picture my veins like great cylindrical halls lined with all the willing and unwilling participants of my mixed heritage. The rabies virus pumped in as if through the vents, weaving in and out, drifting over and under all the bodies inside my body, all the mixed blood in my blood.

📚Anti-Intellectualism in American Life by Richard Hofstadter

I’d previously read The Paranoid Style in American Politics, and seeing Hofstadter’s article version of that text in Lopate’s The Golden Age of the American Essay (2021) brought this one to mind. I’m about 20% of the way through, and at this stage, he’s exploring the relationship between pietism and rationalism in 19th/20th-century American history. Hofstadter was a masterful stylist and illuminating thinker. I thought his distinction between intellect and the intellectual was useful. I like this quote he includes from one of my heroes, John Dewey:

Let us admit the case of the conservative…If we once start thinking no one can guarantee what will be the outcome, except that many objects, ends and institutions will be surely doomed. Every thinker puts some portion of an apparently stable world in peril, and no one can wholly predict what will emerge in its place (45).

Beyond Dewey, quotes like this from the evangelist Billy Sunday are too much:

Jesus Christ could go like a six-cylinder engine, and if you think Jesus couldn’t, you’re dead wrong…Jesus was no dough-faced, lick-spittle proposition. Jesus was the greatest scrapper that ever lived (116).

🍿Karaoke Paradise (2022)

I saw this one at the European Cinema Festival at the Cinemateca in Bogota. It’s a Finnish documentary that follows a woman who travels to bars, nursing homes, and the like in rural areas to host karaoke events. It’s powerful in capturing the power of karaoke to combat loneliness and leave the performer feeling validated and affirmed. I’ve been revisiting some of the old punk rock/hardcore music of my youth, and group chants of the lyrics are a huge part of the live show in that subculture. The idea might be a little different, but it’s interesting to see a similar phenomenon take shape here in terms of the way that participating in rather than just observing live musical performance can satisfy deep emotional and social needs.

🍿 Dark (2022)

I’m on Season Three now. I admit things are starting to go a little off the rails for me. I adore the metaphor of time travel as a vehicle for exploring life’s untaken paths and previous mistakes. The moody atmosphere nicely carries through the entirety of the series, and some of the doubling of scenes at the start of the third season cleverly underscores the shift to a parallel universe. I like the show’s metaphysical reflections on the nature of time, but I might have dwelled for too long in the sectors of formal philosophy that take on those questions for its work in that area to hit as hard for me as perhaps it would otherwise.

Thinking Like a Girl

Credit for the image: Albion British Comics Database Wiki (https://britishcomics.fandom.com/wiki/School_Friend)

“You learned to think like a girl,” she blurted out with a force I hadn’t expected. Then she gestured toward the wine bottle.

“Thinking like a girl.” For a second, I thought of “Throwing like a Girl” by Iris Marion Young, which is a response to Erwin Straus’s “The Upright Posture.”

In his essay, Straus writes: “Upright we are, and we experience ourselves in this specific relation to the world.” In her essay, Young writes: “At a more specific level, however, there is a particular style of bodily comportment which is typical of feminine existence, and this style consists of particular modalities of the structures and conditions of the body’s existence in the world.”

“Finish it,” I said. The brand had been new to me, but the wine had been a hit everywhere I’d brought it. I’d picked up a few bottles here and there as I made the rounds on that trip home. People liked it.

She poured from the bottle, starting with my glass.

“All for you. I have to drive,” I said.

She looked at me dubiously with her head half-lowered. “Half and half,” she negotiated.

I nodded assent, and she filled our glasses. Mine was already kind of full, I thought.

What had started this was that she’d asked about scopolamine, and I’d been explaining how important it was to be aware of your drink when you were out around the city. It was common for people to spike your drink with scopolamine to make it easier to rob you. As the stories went, it made you like a zombie—up and moving around but with no real awareness of where you were or what you were doing. In the morning, you’d have no memory of the night before. You learned to keep a close eye on your drink (drinking like a girl?).

“That’s an interesting…” I trailed off. “I was recently reading, well…” I trailed off again, aware that other people at the table were half-listening. I’d started to say that I’d recently reread Chuck Bowden’s “Torch Song,” and he made a similar point there, but I felt pedantic saying it. “These recognizable patterns, they’re….”

I was floundering, and she offered a hand. “Something like that happened the other day when I was showing a guy around the Town Hall. He was there to install something.”

“Torch Song” is about Bowden’s experience working as a sex crimes reporter. It’s the only essay I’ve ever read like it. I read it after spending two years of my life working at a treatment facility for juvenile sex offenders (i.e., kids who’d assaulted other people, but pretty much all had previously been victims themselves, so you’re as right as you are wrong if you read that clumsy, Orwellian formulation as meaning its opposite).

I took an unintentionally large sip of wine from my glass because I have a tendency of eating and drinking quickly. I surreptitiously scanned the table; attention seemed to have shifted elsewhere as people returned to whatever it was they were talking about with whomever they were talking with. The room looked like it should smell like woodsmoke but actually smelled like food.

She continued: “I was showing him around the top floor, which is kind of like an attic. I realized when I’d walked in that I’d positioned myself so that he was in the door, and there’s only one door. I felt trapped.”

I’d left my work at the treatment facility feeling burned out and cynical after watching wave after wave of kids be perfunctorily shunted through the facility’s shoddy CBT program. The treatment curriculum’s lack of sociological awareness or appreciation for the darker sides of human psychology offered flawed foundations for its already half-assed approach.

Bowden’s is the only account I’ve found that documents the type of psychological unraveling that can follow from exposure to all of that, though my slow-motion breakdown had fewer pyrotechnics than his.

“What did he do?” I said.

“Nothing. We did an awkward little dance getting out, and I took him back downstairs.”

Virtually every door was locked at the juvenile sex offender treatment facility. Freedom of movement was restricted there. As one astute young resident once noted to me, the place was prison with occasional therapy.

“Was he threatening or creepy?” I asked.

For a long time after I stopped working with JSOs, I would pause imperceptibly before going through doors, as though I had to remind myself that they didn’t need to be unlocked. I stopped doing that after a while.

She shrugged.

Upright we are.

Mental 📸: Someday is Today, Phillip Lopate, Dark, The Cruise

A snapshot of inside my mind would go some weird directions today. I woke up this morning and spontaneously thought of this bizarre 1990s documentary of a NYC bus tour guide. I probably saw it in 1998 or 1999 after getting it from Mad Mike’s Video in Wallingford, CT (RIP; that place was incredible). Apparently, it’s the same director who later went on to do Capote with Philip Seymour Hoffman. Amazingly, they have the whole thing on YouTube: The Cruise.

I can only imagine the tours this guy gave. It must have been a very unique way to experience NYC:

“When I went in for my arraignment, the judge said that the problem is that this guy, this current person we’re judging, ran from the police for a month.

Of course, if I could have spoken, I wasn’t allowed to speak, but I would have said: ‘It’s been a lot more than a month. I’ve been running from you people all my life. And I’m going to keep running…and it made me think that, in some ways, from the perspective of molecular biology, we have the same infrastructure as plants.’”

I feel like I’ve slipped into full productivity-nut terrain. I’ve covered quite a bit of ground in that space, so I try to prevent my focus on productivity strategies from crowding out my actual productivity. Still, I like to incorporate a productivity book into my reading diet every few months. It provides a nice tune-up. I’d heard Someday is Today was good, and I really liked Dicks’s book on story, so I figured I’d check it out.

There are a lot of connections with my personal life--Dicks is a full-time teacher in my home state of CT, and one of the key anecdotes in his origin story is his experience of being robbed while working at a McDonald’s in Brockton, MA, twenty-five or so years ago. I did my first year of service with AmeriCorps in 2007, so I know a little about the town.

The writing style and humor didn’t always resonate with me—in some places, the voice veers into “high school valedictory address” territory that isn’t quite my cup of tea. Still, even from the perspective of a time-optimized guy, Dicks’s level of time optimization and productivity is insane. Sometimes I agree, sometimes I don’t, but it’s hard not to admire his level of achievement and commitment to living the most meaningful life he can.

Some of his stories were inspiring; some tips were useful: per his suggestion, I’ve started standing on one leg while flossing to take the extra opportunity to strengthen my core/balance. This makes me feel completely absurd and “eccentric” in a bad way, but I think it’s helping.

Questionable flossing habits aside, I felt like I took a lot from his advice to be a “criminal.” His point is that many rules are pointless or more flexible than they appear. Often not following relatively superficial rules can save a lot of time and energy that can be put into more substantial undertakings. More concretely, he recommends carrying what he calls a “burglar bag” of useful materials that you can draw upon to steal back your time when it’s being wasted.

I’m something of a recovering rule-follower. I wasn’t much of a rule-follower as a kid, but I became one as an adult for reasons likely related to some guilt complex or other I only vaguely understand. More recently, I feel like I’ve started to see the wisdom of being a micro-petty criminal of the caliber Dicks suggests. So, I guess I’ll start to pack my productivity burglar bag.

📚The Golden Age of the American Essay: 1945-1970, edited by Phillip Lopate

Lopate is a fantastic essayist in his own right, and I adore the treasure troves that are his essay collections. I’ve worked through nearly all of The Personal Essay, as well as selections from most of his other edited volumes.

However, this is my first time looking at The Golden Age. Paul Goodman’s essay “The Universal Trap” stood out to me. I previously only knew of him as a somewhat forgotten 1960s figure, but his essay on schooling ended up being more nuanced and better written than I’d expected. Richard Hofstadter’s “Paranoid Style” is in there, which is a delight to read and left me sufficiently inspired to pick up Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, which I’ll probably start later this week. Clement Greenberg’s “Modernist Painting” was illuminating, particularly in its reflections on Modernism’s awareness of the essence of painting being the two-dimensional art form. The dimensionality of art (2D vs. 3D) has been on my radar since reading Michael Clune’s Gamelife, which has a completely fascinating discussion of the aesthetic and philosophical implications of 2D vs. 3D art.

🍿 Dark

The German Stranger Things. What it lacks in style vis-à-vis ST it makes up for in depth. The painterly quality of its visual aesthetic stands out. A lot of cool interweaving plotlines—I feel like I need a whiteboard to keep track of the relations between the characters as we follow them across various historical periods. Allusions to Nietzsche, Freud, and the heavy metal band Kreator stand out.

A Note for the Guy I Impersonated in 2003

Photo Property of the Author (sort of)

I wasn’t sure if she meant me or the guy I was pretending to be when she said, “You have beautiful eyes.” She’d been staring at the ID for a while, scrutinizing it carefully and hadn’t looked up when she’d spoken.

It could have been either of us or both—maybe the way one of us looked had affected how she’d seen the other. We both had blue eyes, which had been one of the main arguments in favor of me choosing him to pretend to be.

It was a strange case where our identities—mine and the guy I was impersonating—converged.

“Thank you,” I’d finally said, having no real choice but to accept the compliment as my own. Clearly dubious, the woman had apparently decided I’d suffered enough and finally decided to ring up my order, leaving me to slink off to my other underage friends.

My fake ID. I remember my friend flipping through a small stack of IDs before settling on the one she had: Andre Y---.

Where had she gotten all of those IDs? I must have asked, but twenty years later, I don’t remember.

For a period, that became my nickname with my friends: Andre. I was Andre.

I wasn’t Andre for long. For some reason, an ID that said I was six inches taller than I was and of a different ethnicity never worked that well. I used it to get into some bars and concerts, and I think I bought beer with it a few times. It was always nerve-racking. People let it slide, but I don’t think anyone ever believed I was the guy on the license. Besides, I was almost 21 by the time I got it, so after a short span of appealing to the kindness of strangers to avoid arrest, I was able to retire it in favor of my real ID.

It never occurred to me to ask who the real Andre was, or if there even was a real Andre. I vaguely remember my friend John saying at the time that he knew the real Andre, but I didn’t believe him. I guess I’d assumed there wasn’t a real Andre.

It popped into my head the other day, and I decided to do a quick Google search. It turns out there was an actual Andre. For a few months in 2003, I was going around pretending to be him.

Reading about the actual Andre reminded me of the scenes in war novels where characters find a picture of an enemy soldier from their civilian life. The Naked and the Dead has a scene like that. Suddenly, Andre wasn’t “Andre”—he was a real guy with friends, family, a career—a whole personal history.

In hindsight, maybe John had known him. Andre and I could have easily crossed paths. He reminds me of a lot of people I knew during that time. He briefly went to the same local college many of my friends attended. He lived in a town I’d often visit for its record shop. Apparently, he dabbled in skateboarding, which was a big thing for me during that period.

There’s not a ton I can say about the actual Andre for certain, but I can be sure that at some point on May 23, 2001, the real Andre had gone to the DMV and had his picture taken. Overall, things seem to have gone well for him after that: he took up a trade after leaving college early, got married, and had two daughters.

At least, they went well until they didn’t. Most of what I know about him comes from obituaries. He died young in 2018. The obituaries don’t say how. Often that’s done when the person died for a particularly unfortunate reason. I hope that wasn’t the case for him.

Someone hosted an online fundraising drive after his death. The money was supposed to support his family and pay for his burial expenses. I took an inexplicable sense of pride in seeing that it had exceeded its $10,000 goal.

His expired license is a record of a man who no longer walks the Earth. Despite this, his memory kicks around in the head of another man he’d never met and now lives on a continent he likely never visited.

If he’d lived longer, I would have told him the lady who worked at Teri’s Package Store in Higganum, CT, in 2003 said he had nice eyes. I’d be willing to turn the compliment over to him. After all, she’d been looking at his picture when she’d said it.

Mental 📸: Mailer, Possession (1981), Cannibal Holocaust (1980)

I didn’t include it in this list because I just started it, but Dark seems promising. It was presented to me as a blend of Stranger Things and Twin Peaks, which is quite a combination, so I’m going in with high expectations (at least based on the first and final TP seasons; the stuff in the middle was too much for even a Lynch fanatic like myself).

🍿Cannibal Holocaust (1980)

Along with Faces of Death, this one had been something of an urban legend for me. I saw they had it on Kanopy and finally got around to watching it.

It’s famously controversial for its potential racism and authentic mutilation of animals. Despite its best efforts, it certainly reflects the biases of its time, and it’s hard for me to justify the torture of animals for the sake of art. At the same time, the film’s anger is palpable, and I can understand the rage that could lead to the use of grotesque measures to underscore the grotesquerie of Western arrogance, ignorance, and violence. From a cinematic standpoint, its help in pioneering the modern found footage approach to cinema was more innovative than I’d expected.

🍿Possession (1981)

I’m unusually patient with maximalist art that fails from overreach. This one weaves together many of my pet tastes: the Soviet bloc, body horror, doppelgangers, impressionistic representations of mental health challenges, etc. It feels genuinely deranged, which is part of its artistic merit but also makes it uncomfortable to watch. Even I felt like it started to get a little top-heavy, and any film that tries to do that much is bound to spread itself thin. I guess I ended up being of two minds about it; it might be worth watching it again.

I was surprised to see that this Massive Attack video pays homage to the film’s subway scene. Pretty cool!

📚The Naked and the Dead (1948)

I finally finished off this one. I thought the final scenes were deftly handled, and Hearn’s death in particular was superbly rendered. The sections in which the men carry Wilson down the mountain were some of the strongest of the entire novel. In the end, the book’s cynicism felt earned, and I found it to be genuinely disheartening. Passages like the following hit hard:

Only…for an instant when he [Cummings] heard the news of Hearn’s death, it had hurt him, wrenched his heart with a cruel fist. He had almost grieved for Hearn, and then it had been covered by something else, something more complex. For days whenever Cummings thought of the Lieutenant he would feel mingled pain and satisfaction.

Hot dog, indeed.

Better get Into What you Gotta Get Into: Misogyny and Institutional Failure in Barbarian (2022)

Barbarian (2022) is a frothy film of themes like intergenerational trauma, incest, and urban blight.

The line on Barbarian is that it’s best experienced when you go in blind, and I think that’s right. The plot goes in some genuinely surprising directions, and much of its pleasure and intelligence is in those twists and turns.

With that in mind, I wouldn’t recommend reading a blog post about the film if you haven’t already seen it, but here’s a quick summary if you prefer Cliff’s Notes to roller coaster rides:

A woman, Tess (a fantastic Georgina Campbell), arrives at an AirBnB in a dangerous, largely abandoned neighborhood in Detroit (Brightmoor) in the middle of the night. As it turns out, the AirBnB has been double-booked. Tess is initially suspicious of Keith (Bill Skarsgard shining), the other guest, but as it turns out, he’s well-intentioned. Less well-intentioned is the monster (Matthew Patrick Davis) lurking in the basement. The monster is shown to be the product of generations of incest by a serial rapist and murderer, Frank (Richard Brake), who owned the home prior to the neighborhood’s decline. Meanwhile, in the present day, the home is visited by its current owner, AJ (Justin Long), a disgraced Hollywood actor now facing a rape allegation. While AJ hopes to sell the home to scrape up money for his legal defense, his fate comes to overlap with Tess’s as they both attempt to escape the monster.

Light viewing (which I mean both seriously and in jest).

Commentators have rightly pointed out that the film investigates different forms of misogyny. It nicely unpacks how misogynistic abuse can lead to successive generations of trauma (admittedly the plot mechanics of having multiple inbred generations that result in hyper-strong mutant monster offspring take shape across 30 years requires a little suspension of disbelief, but, hey, being cavalier about literal accuracy is one of the appealing features of popcorn sociologizing). It captures the heartbreakingly obsessive, smothering form of love that an abusive relationship can foster in its victims. It sets up Frank and AJ as corollaries while underscoring the “monsters” that their hatred and violence produce as a result of them being monsters themselves.

In this regard, as absurd as this sentence is about to sound, the final scene of the monster’s death is touching and is effectively juxtaposed with Frank’s death: while both die from a gunshot to the head, Frank’s is done selfishly when he realizes he has finally been caught while the monster’s acceptance of its death is an act of mercy to set Tess free.

I wouldn’t call it a subtle film per se, but it’s suggestive in a number of ways. For example, it stood out to me that when we are first introduced to AJ, he’s shown singing the lyrics to Donovan’s “Riki Tiki Tavi”:

Everybody who read the Jungle Book

Will know that Riki Tiki Tavi is a mongoose who kills snakes

When I was a young man, I was led to believe there were organizations

To kill my snakes for me

i.e., the church, i.e., the government, i.e., school

But when I got a little older, I learned I had to kill them myself

I said, Riki Tiki Tavi mongoose is gone

Riki Tiki Tavi mongoose is gone

Won't be coming around for to kill your snakes no more, my love

Riki Tiki Tavi mongoose is gone

It’s a great song and is superb musical accompaniment to AJ driving in his retro convertible along the California coast.

Beyond that, the lyrics are arguably less subtle than the film: our institutions have failed us, and we have to solve our problems ourselves. No Riki Tiki Tavi working on our behalf. I imagine this was a more striking sentiment when the song was released in 1970. Now, more than half a century later, our institutional cynicism is (rightly) so thick that the song can seem almost quaint.

The link between the song and the film’s thematic content is obvious: Barbarian is pretty clear that institutional failure has contributed to the utter desolation of Brightmoor (and, by extension, a sizable part of American society). Perhaps the most overt illustration of this is the police officers’ blasé and bemused responses to the heavily traumatized Tess after she has escaped the monster and is begging for help. Spoiler alert: the officers don’t help.

In that sense, the Donovan song was an interesting choice to introduce us to AJ. If you think about it, AJ’s situation might reflect the only case in the entire film of our institutions at least kind of working. AJ is guilty of the rape, and he’s paying a price for it: his pilot has been canceled, he’s facing bankruptcy, his family seems skeptical if not horrified, and his lawyer remarks on a “high probability” that he’s about to be arrested.

Of course, this isn’t to say that all is well or that our institutions will carry through at the end of the day, but his case is markedly different from Frank’s, who is never formally held accountable for his years of rape and murder. In the end, AJ is dealt with via street justice on the part of the monster, though his life was trending downward because of his self-delusion and entitlement well before the monster finally gets around to crushing his head.

What to make of that? It could be a statement on social class—AJ’s victim was a Hollywood actress, while Frank’s multiple victims seem to have been working-class people. That would certainly fall in line with the film’s approach to gentrification and urban neglect. Another way to come at it would be to see it as nuancing the film’s treatment of institutional failure: we have occasional pockets of high-profile success in reining in our wildly unchecked social problems while leaving the majority of cases unaddressed. A third of many potential interpretations might give us more of a psychoanalytic account of the monstrous impulses locked away in the metaphorical basement (Frank), which are generally tolerated barring an occasional over-reach into polite society (AJ).

That’s just a start. The film is suggestive enough that we could take it a number of directions while being vague enough to not point us toward much of a resolution here. And that’s fine. The questions are enough. Director Zach Cregger might not be Riki Tiki Tavi, but in these desperate days, maybe popcorn horror can help guard the garden. Someone has to.

Mental 📸: Fritz Lang, Kelly Reichardt, Mailer, Steven Pressfield

Strange last week or two—I’ve been super busy with client work and also really anxious. As a result, my media consumption has slowed slightly, but I’ve still been able to consume some great stuff:

This was my first time seeing the more complete version that was released in 2010; I’d previously seen one of the abbreviated versions in a film history class I took years ago. It was much weirder and angrier than I remembered. A lot of strange details, like the pentagram in Rotwang’s laboratory, stood out to me. Needless to say, it’s absolutely visually stunning.

I know Lang later rejected the film’s conclusion as simplistic, and of course that’s true. Thinking about that made me realize how the viewer can so easily slip into a certain condescension when viewing historical sources—I didn’t consciously think of the conclusion as simplistic (more “cute” or “quaint”), though of course if a modern artwork put forward such a naïve view, I would likely need to be hospitalized from my tremendous eyeroll.

I adore Kelly Reichardt’s work, and I was thrilled to see her pair up again with Michelle Williams. I thought it was a fantastic success. The realities of creative struggle and failure stood out to me, though it was the touching treatment of the complex relationship between two frenemy creators that carried it.

🎙️ Various Steven Pressfield interviews

I’m not always on board with a literal interpretation of Pressfield’s stuff on past lives, the muse, etc., but a lot of what he says resonates with my experience of the psychology of creativity. His writing advice is super helpful—both directly and indirectly. It’s also pretty nuts that his agent is 98 and the same guy who originally sold On the Road.

📚 The Naked and the Dead (1948)

I’m about 75% of the way through it now. As always, I adored the “time machine” segments. Red’s section stood out to me, and kind of reminded me of sections of Dos Passos’s USA Trilogy, and I have a soft spot for that one (Lethem’s The Brooklyn Crime Story seemed to have some resonances of that text, which I thought was cool). One of my favorite details is Mailer’s consistent hint that General Cummings might not be clear on his own motivations in shaping military policy around his petty conflicts with a subordinate (Hearn)

“Semicircles” (fiction)

I was reading back through some old stuff and came across this fragment. It’s a section from a longer piece. The longer story didn’t really come together, but I kind of liked this section. Maybe I’ll build something around it.

——————————————————————————————————————————

“The fields are dangerous” is what Jimbo thinks he hears his father say. It is one of the times he is left guessing whether the old man is trying to clue him in on the fact that he knows more about his son’s lifestyle than he lets on. Now and then an unexpected clarity surfaces from behind the old man’s ostensible incoherence and flashes of belligerence.

“Sure,” Jimbo says. He puts the bag of nuts down between the legs of his yellowed lawn chair. He’s seen strays drink from the furrows dug by the chair’s slatted legs, but only a few flies are at the bottom of the dried-out troughs now.

“Not in the dirt.”

Jimbo raises the bag to his lap. He shoots forth a dribble of chalky, dense spit. It joins the similar mounds that make a wide half-moon around the front of the two chairs.

“Hey--” the old man starts before going silent as he takes a massive sip from his beer. It is unclear if he had interrupted himself with the sip or if the sip itself had been the point. He lets out a loud burp.

“Putting ‘em back, huh?”

“Look, Son, I’m not drunk. If I was drunk I’d be going like this.” He holds up his hand to demonstrate severe tremors.

“Yeah, and if you was really drunk, you’d be going like this,” Jimbo says before shaking his whole body.

“You’re looking like you’re trying to kill me,” the old man crows. He retrieves the coin and sends it back through the Coke machine. Another cold one comes out as the quarter reappears where it had been. His dad’s rigged Coke machine is a great conversation piece with his friends, though none had seen it.

“Phone! Phone!…Jimbo: phone!”

“I said I’m coming,” he shouts even though he hadn’t said anything. He jogs across the backyard and bounds up the cracked cement steps before throwing the screen door open hard enough to contribute to the dents that mark the house’s faded olive green facade.

“I told you watch it with that,” his mother says in a harsh whisper, taking him by the shoulder with a finger in his face.

Jimbo grunts and takes the phone from where she had left it on the counter. The kitchen smells like sweat and stale smoke.

“Hello,” he says in a now deeper voice.

“Yo, I’m coming around,” the voice on the other end of the receiver says.

“…don’t think anything of shitting it up,” in his auditory periphery Jimbo catches the last snatch of what his mother is saying. She sags as she walks toward the sink.

“Now?” Jimbo says.

“Yeah. Coming around.”

Jimbo hangs up the phone.

She is saying something about his father to herself. He slows upon hearing this. Most times the old man was agreeable enough if you didn’t get in his way or stop him from drinking.

“Tommy’s coming to get me. We’re going out.”

“Out?” she turns from the small, curtained window above the sink to face him.

“Yeah. Out. With Tommy.” He brushes past her as he heads for the front door.

She puts her hands to the same thin blond hair she shares with her son and sighs. As he grabs the door handle, he sighs as well, making them seem contagious like yawns.

He adds another dent to the house on his way out, and then pauses to look toward the Coke machine in its cul-de-sac at the end of the driveway. Sometimes his father will take unexpected offense to things like that. Sensing no movement from the Coke machine, he sprints up the dirt driveway, rushing to the ragged edge of its opening.

The Work of (Not) Mourning

One of the few things as certain as my death is yours. Part of what it means to live is to deal with the deaths of others—those we love, and those we don’t.

I made it through a good part of the first half of my life without losing too many people close to me. That luck has run out over the last few years (weirdly, I wanted to phrase that as “that long overdue debt has come due,” but why think of it as a “debt” and to whom or what would it be owed?). I loved some of those people deeply, others I didn’t know very well, and still some I’m not so sure I liked much at all.

The result is I’ve spent a good part of the last year trying to figure out how to mourn, who to mourn, and when to mourn. Indeed, while mourning might be universal work, we don’t get much guidance on how to do it. Our educational institutions won’t touch it, and most of us get very little broader cultural support in that area.

Once I had a professor from overseas who pointed out how weird it was that American society provided so little education on romance or sex. Those are such important parts of life, he reasoned, but we leave people to figure them all out on their own. A similar point could be made about mourning. Grieving is unavoidable and important for ethical as well as psychological reasons, but we have few reliable norms, practices, or inherited wisdom to help us face death in any of its manifestations.

In thinking about this, one book that came to mind was Derrida’s The Work of Mourning, which I’d first read years ago in grad school. The construction of the book itself is interesting—it’s an edited collection of diverse texts (e.g., eulogies, funeral orations, essays, and letters) that Derrida wrote after or about the deaths of his friends. Derrida was part of a fascinating generation of thinkers, and he outlived many of them. He wrote beautifully about his friends when they were gone.

It's a wonderful book, and it really shows Derrida wrestling with the ethics of how to mourn. In a conceptual strategy typical of Derrida’s thought, he notes how in mourning we are enmeshed in puzzling contradictions. These puzzles generally don’t have solutions; often the best we can do is to try to avoid getting knotted up in them. It’s as hard to mourn well as it is to live well.

For example, Derrida writes about the ethical responsibility we feel to honor a friend’s death by saying something about them. He’s right, of course, and that imperative can feel more like a compulsion. However, he also points out how hard it is to do that right. Is it possible to find the right words to express the depth of genuine loss? If words are bound to fall short, then is the solution not to speak? However, if that silence itself is intolerable or unethical, then do you content yourself with speaking inadequately? If so, then what types of inadequate speech will be adequate?

Lunch is on me if you have an answer up your sleeve. I could certainly use the help.

Derrida’s text focuses on mourning friends. Friendship is a very specific type of relationship. While he acknowledges some stormy moments, at least in The Work of Mourning, he limits himself to writing about people he ultimately liked and will miss.

In that sense, I’ve found myself wondering what puzzles might be true of other cases of mourning. Different relationships will be mourned in different ways. Mourning a parent is different from mourning a friend—or a respected adversary. Mourning a healthy relationship is different from mourning an unhealthy one.

I’m particularly curious about that last one—how to mourn a relationship that wasn’t joyful. Derrida talks a lot about “interiorization” in the act of mourning or the way you internalize the memory of a person. In a different way, I briefly noted this type of experience in a previous post. When you engage with someone, there’s a way you draw their voice and perspective into you as an enduring image. It’s a type of memory you breathe life into, like some strange Pinocchio of people you’ve known. Of course, you’re behind the whole thing, but it can certainly feel like the image acts of its own volition. Think of what it feels like when you suddenly just know what an old friend would think of something you’ve said or done.

Given that he’s talking about friends, Derrida of course discusses interiorization as a way of keeping the dead alive inside you. I like that idea. But interiorizing someone isn’t always what you want—there are plenty of voices in my head that I wish I’d never let in (though I guess you don’t always have much of a say in it). Interiorization is at the heart of mourning, and it gets an interesting twist in the case of mourning an unhealthy relationship: it seems to me that part of mourning a non-joyful relationship is to interiorize the person just enough to remember the failures of the relationship without letting them in too deeply. Their voice can be poisonous.

Just like in the examples Derrida gives of mourning a friend, mourning someone you don’t miss is important for the same ethical and psychological reasons. Whitewashing the relationship of its toxicity is dishonest, unfair to the world, and harmful to your own growth for many reasons—not the least of which is that you need to remember enough to avoid future experiences of abuse.

Is such a thing possible? How do you handle that contaminated emotional material without being contaminated? How do you pay proper respects to the death of one whose voice you should interiorize without really interiorizing? How do you mourn without mourning?

Mental 📸: After Yang, John Franklin Bardin, Mailer, The Trap

They’ve been doing work on the apartment above mine, which has made sleep a little rough. I’m trying to look at it is a meditative practice to see if I can hold a thought in my head while trying to work in a construction zone. Fingers crossed they wrap up whatever they’re doing this afternoon.

A portrait inside my head:

🎬After Yang (2021)

I adored Kogonda’s Columbus, which I’d first seen at the Brattle and recently rewatched, so I was really excited to see this one. It has plenty of big ideas, though I wish it’d had more if it’s going to take that tack. Still, Kogonda is a master of the little moments, and it’s the little moments that make it. My favorite scene might be when Mika wakes up to get a glass of water and interrupts her father watching Yang’s memories, which was beautifully executed.

🎬The Trap (2007)

Adam Curtis’s stuff is always fascinating. I love the idea of investigating how our conceptions of freedom have led to important social outcomes. The film paints with incredibly broad strokes, and it’s easy to quibble over a million details—both historical and conceptual. Still, it’s provocative, and works for a popular audience rarely if ever take on this type of important approach.

On a personal level, it felt very characteristic of the intellectual climate of its time, which for me lines up with undergrad and my first experiences reading topics covered in the film like Isaiah Berlin, game theory, US foreign policy in Iraq, etc. As strange as it might sound about a film like The Trap, it had a certain nostalgic value for me.

📚The Deadly Percheron by John Franklin Bardin (1946)

I read this weird little book that plays with the potential depth of pulpy noir over the winter. I’ve been thinking a lot about memory recently, and this passage came back to me:

“Memories exist whole in the mind; to put them down in words demands sequence, a sense of time and space, of then and now. But when one remembers an event that belongs to the far past and relates it to another happening that belongs to yesterday, these memories exist together simultaneously—they are both, for a moment, now, not then. And so it had been with me when I stretched out on the bed in my small room, shut my eyes and with the blotting out of sight closed down upon the present, let the lost past seize me and hold me fast. I saw it whole, lived it all again – not in an hour, or even in several minutes, but in a single, incalculable instant….” (35)

📚The Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer (1948)

I’m about 25% of the way through it. There’s much more to like here than I expected. Of course the combat scenes are beautifully rendered and illuminating for historical reasons. I would make a similar point about the book’s account of the antisemitism and covert fascism in the US army during WWII. But it’s really the scenes that explore the soldiers’ backstories that resonate with me; I thought the “time machine” chapter on Croft was particularly effective and dark This is my first time reading TNATD, and I’m curious to see where it goes.

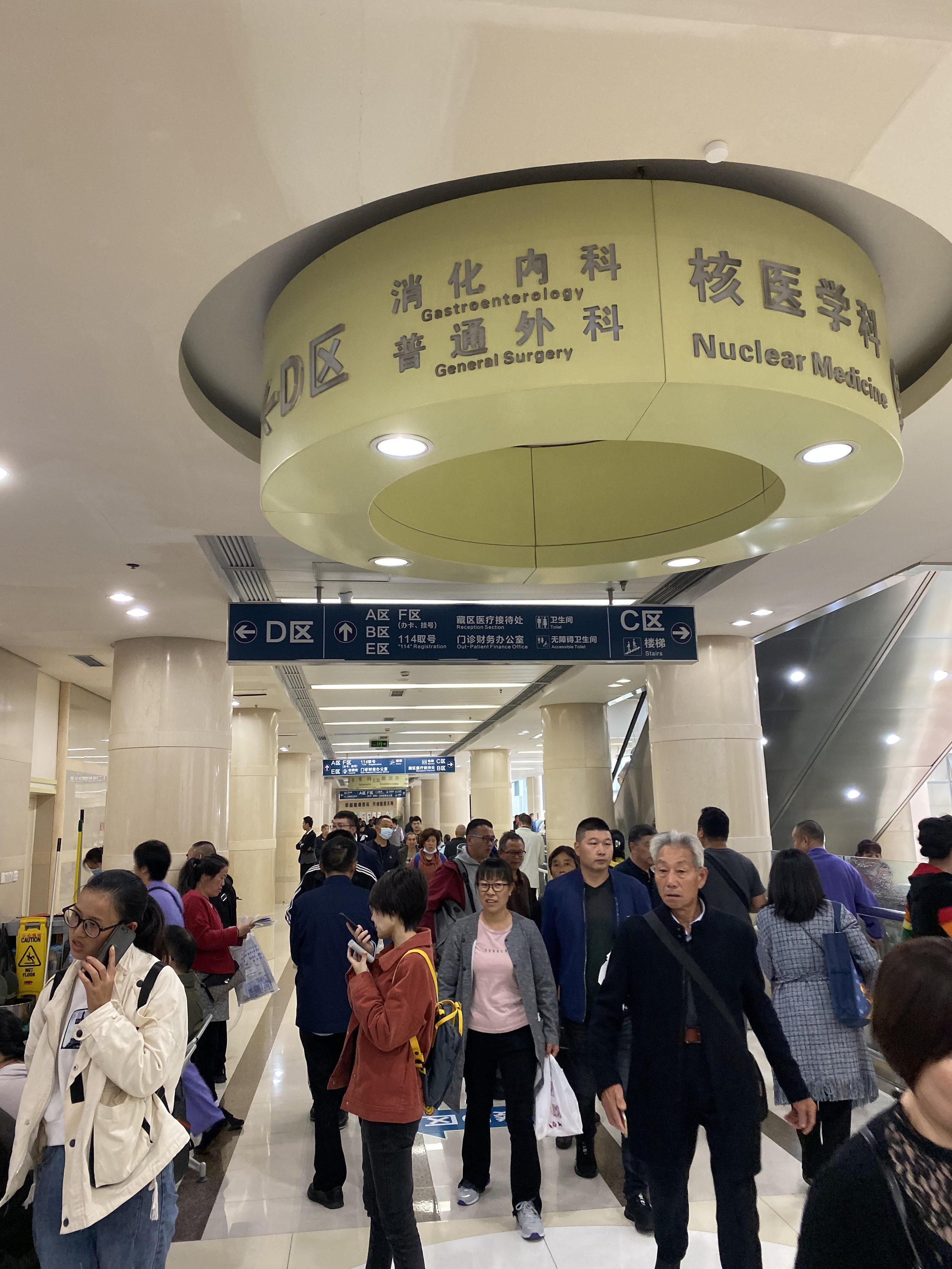

People Mountain, People Sea

I’d been in pain for nearly three months when I finally agreed to visit the hospital.

“You are being selfish, racist,” my girlfriend, Xin, had said when I had rebuffed the idea of visiting the clinic. She worked two side hustles in addition to her full-time job in arts management. I knew she’d spent over an hour handling the red tape necessary for a foreigner to see a doctor in China. It had been hard on her for me to be homebound and in constant pain.

“Well, he’s one of the best, right?” I finally conceded.

I arrived at 1:30 p.m., though my appointment wasn’t until 2:30 p.m. When I got to the office, I waited in line to show my ticket to the woman behind the counter. Smiling and nodding, she signaled that I was in the right place. I turned and began to drift toward a line of seats. A woman, another patient, touched my arm to catch my attention. “This is next,” she said, pointing to a small kiosk that I was walking away from.

A security guard came over as he saw me approach the kiosk. He helped me run my card through the machine and handed me a slip with the details of my appointment.

“Do you speak Chinese?” he asked in Mandarin.

“Very little,” I said in Mandarin, shaking my head doubtfully.

He looked worried. “Very little,” he repeated now in English.

“I have a Chinese friend, and she will help me. I am waiting,” I said slowly and deliberately.

“Oh, very good. You will wait, and your friend will help. The doctor will help,” he said, delighted. He gave a thumbs-up. I smiled.

I took my receipt and went to hover behind a row of chairs in front of the electronic billboard that listed the upcoming names and appointments. My name wasn’t up yet. Nervously, I kneaded the wadded-up tissue I’d used to clean my hands after using the bathroom. I had been warned that bathrooms in Chinese hospitals often didn’t have soap or paper towels, so I’d brought hand sanitizer and tissues. It had been good advice.

The Chinese have an expression for crowded places: people mountain, people sea. The room was crowded, and I was jostled by shoulders and elbows. People shouted into cell phones, shouted at each other, and shouted at video games they played on their phones.