People Mountain, People Sea

I’d been in pain for nearly three months when I finally agreed to visit the hospital.

“You are being selfish, racist,” my girlfriend, Xin, had said when I had rebuffed the idea of visiting the clinic. She worked two side hustles in addition to her full-time job in arts management. I knew she’d spent over an hour handling the red tape necessary for a foreigner to see a doctor in China. It had been hard on her for me to be homebound and in constant pain.

“Well, he’s one of the best, right?” I finally conceded.

I arrived at 1:30 p.m., though my appointment wasn’t until 2:30 p.m. When I got to the office, I waited in line to show my ticket to the woman behind the counter. Smiling and nodding, she signaled that I was in the right place. I turned and began to drift toward a line of seats. A woman, another patient, touched my arm to catch my attention. “This is next,” she said, pointing to a small kiosk that I was walking away from.

A security guard came over as he saw me approach the kiosk. He helped me run my card through the machine and handed me a slip with the details of my appointment.

“Do you speak Chinese?” he asked in Mandarin.

“Very little,” I said in Mandarin, shaking my head doubtfully.

He looked worried. “Very little,” he repeated now in English.

“I have a Chinese friend, and she will help me. I am waiting,” I said slowly and deliberately.

“Oh, very good. You will wait, and your friend will help. The doctor will help,” he said, delighted. He gave a thumbs-up. I smiled.

I took my receipt and went to hover behind a row of chairs in front of the electronic billboard that listed the upcoming names and appointments. My name wasn’t up yet. Nervously, I kneaded the wadded-up tissue I’d used to clean my hands after using the bathroom. I had been warned that bathrooms in Chinese hospitals often didn’t have soap or paper towels, so I’d brought hand sanitizer and tissues. It had been good advice.

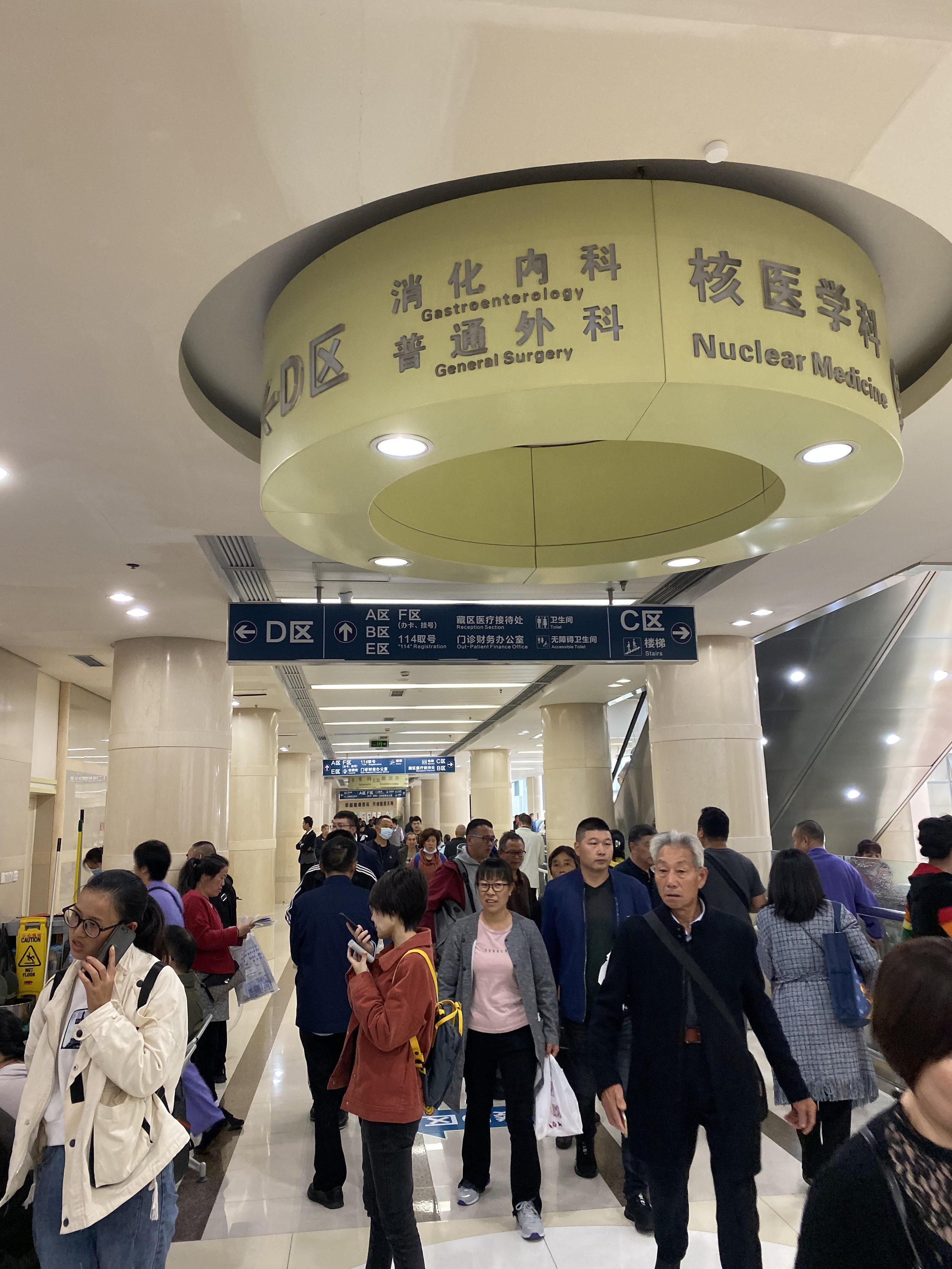

The Chinese have an expression for crowded places: people mountain, people sea. The room was crowded, and I was jostled by shoulders and elbows. People shouted into cell phones, shouted at each other, and shouted at video games they played on their phones.

Xin arrived at exactly 2:30 p.m. She had taken the afternoon off from work and dressed nicely for the day, wearing high boots and a cool hat

“You look great,” I said.

“I know,” she said, smirking.

We sat together and she browsed through Taobao on her phone as I explained my questions while looking over a short write-up that I’d done before visiting the Western medical clinic in town a few weeks before.

“Do you think I should get this bag?” she asked, gesturing towards the phone.

“I’m really not sure,” I said.

A person came over to sell us some sort of liquid cleaner. I’d seen the routine at tea houses in town: the salesman would first draw on their shoes with a ballpoint pen before demonstrating how quickly the cleaner would remove the ink.

“Bu yao,” I said somewhat fiercely. The guy moved on to the people sitting next to us.

“Do you like the yellow?” she asked, pointing again to the bag.

“Sure,” I said distractedly, standing to see if my name had come up on the screen. I noticed it at the bottom: Jason Hamilton Piers.

“So,” I said, “I have one key question for him: does he see evidence of a new hernia. At the other clinic they mentioned I might have the start of an incisional hernia. That’s also the advice I’m getting online. I’d also be curious to know his thoughts on hernia mesh removal. I know it’s new and controversial,” I said.

She nodded.

We entered the hallway and lined up in front of the examination room. I could see inside and recognized the doctor from his picture online. Xin peered in, and what looked to be the middle-aged husband of the couple ahead of us eased the door shut, gently closing it in her face.

The hallway was as loud as the waiting room, with people darting in and out of examination rooms. The people inside would shout back that they weren’t finished yet. The room was small, so we were only a few yards from the doctor. I peered around nervously. She noticed.

“It’s crowded. This is the best hospital in all of Sichuan, and Sichuan is one of the biggest provinces. If we went to a country hospital, it would be slow and quiet,” she explained, reading my mind. “This is an expert. He teaches medical students at Sichuan University, so a lot of people want to talk to him.” I tried to see it her way: there was a lot of demand for the man’s time.

Eventually, a young woman, likely a med student, opened the door and motioned for us to enter as the couple walked out. We walked the four feet to stand at the doctor’s table.

“What is wrong with you?” he said to me in English. “You have a hernia?”

Xin released a nervous stream of rapid Mandarin that I didn’t follow. The doctor cut her off. “He’ll check for a hernia,” she told me.

I kept my back to the door, which I noticed was still open, and lowered my pants just far enough for him to be able to touch my bare abdomen

“Cough! Cough!” he barked. He palpated my abdomen. Xin said something.

“Mesh? Mesh?” he shouted.

I nodded and Xin said something else. The exam concluded. We had been in the office for roughly 3 minutes.

“Shi-shi,” I said stupidly as we walked out.

In the waiting room, Xin suggested we sit to discuss the meeting. “He noticed a lump. He said a hernia can lead to a lump.”

“Right,” I said.

“But sometimes you can have a lump after surgery, and there is nothing that can be done about that.”

“Definitely. I had my surgery twelve years ago, but I didn’t have a lump until three months ago.”

“He said you have been in pain for a long time, and we should go back if you have a hernia. Meanwhile, he says we should go to the pain clinic because there is nothing you can do for problems with hernia mesh.”

“What? That’s not true.”

She shrugged.

“Wait, what? What was that?” I said, my voice rising. “We saw the doctor for like two minutes. He didn’t answer any of our questions.”

“We should go,” she said, standing. “Have you had lunch?”

“Idiot,” I said while looking in the doctor’s direction. I stood and considered going back into the office. I’d already lost my cool in China in a way I never had in the United States. A few months before, back when I was able to walk without pain, I’d had an outburst when the guy in front of me had smirked after allowing a friend to cut in line during a long, hot wait to get down from one of the lower summits of Mount Hua. It was disorienting to see how quickly the easy arrogance of my scholarly poise could evaporate.

“I think we should go,” she said again. “Do you want to see the campus of the medical school?”

“That guy was a hernia specialist? An academic and professor in the medical school? Are you serious right now?”

Xin got quiet. “You don’t understand.” She paused, and then it rushed out: “Maybe next time go with someone else, someone like Brother Xiang or Brother Lu. They will want to help you. They are men, and they are rich. Maybe he would have talked to us for longer if we had been with them”

“Money?” I shouted. “We are talking about people’s health, for Christ’s sake. I’ll pay him three times what we just did for a reasonable standard of care.”

“You don’t understand. You are not used to this.” She paused. “There is a gap between us.”

The sea of people swarmed around us. I lowered my eyes. “Thank you for trying to help me. We tried. We did the best we could.”

We were both quiet as we zig-zagged through the crowds and made our way out. Outside, we stopped on a corner. I took out my phone to call a Didi. People zoomed by on electric scooters, bicycles, and mopeds. Xin stared at the ground. My abdomen hurt.

“We have a lot of people. It is hard to make sure that everyone has what they need. Rich Chinese go to the United States for healthcare, or they use connections. You can go back home. The doctors there will see you because you are from their country,” she said.

I held up my phone to indicate the Didi was arriving.

She motioned with her head: “We should go into the street. I don’t want him to drive off if he doesn’t see us.”

I followed her into the crowded street, unsure if I was lost on the mountain or lost at sea.