Attraction and Aesthetics

I saw Andre Aciman give a fascinating reading some years back at the Harvard Bookstore. This was probably 2017, and I believe he was promoting Enigma Variations, which seemed great, but I still haven’t read despite loving Aciman’s work.

During the Q & A period someone asked the classic question of how he was able to write so insightfully about LGBTQ+ characters when he identified as straight. As I recall, the responses were much of what you’d imagine: empathy, artistic imagination, the variability of sexual desire. Good answers, all of them.

Aciman has given similar answers to that question elsewhere, particularly regarding the fluidity of sexual desire. Of course he’s on to something. One likes to think that it would be common sense by now that crude categories such as “straight” or “gay” barely scratch the surface for many if not most people, but that optimism would be sociologically inept. Really, even to say sexuality is “flexible” doesn’t speak to the half of it. Humans have all manner of desires of different durations, types, levels of conscious awareness, etc. We’re complex.

Deepening the point, it occurs to me that there are types of attraction just as much as types of people to be attracted to. It’s easy to slip into thinking of attraction itself as uniform, as though we have X units of the substance “attraction” that we then assign to greater or lesser degrees. But that’s too simplified. Attraction itself isn’t just one thing. There are different species or forms of attraction. It might even be that each experience of attraction is radically singular and particular (while perhaps reflecting more generalizable underlying patterns).

What is “attraction”? What does it mean for something to be “attractive”? Working out a definition would take some elbow grease, but it would have something to do with having a pleasing quality (or qualities) that draw(s) one toward it. In that sense, in the Passions of the Soul, Descartes describes attraction as a combination of love and desire fed by our impulse to move toward beneficial things. Even just within the terms of Descartes’s typically stark, mechanistic definition, it’s easy to think of how different configurations or allotments of love and desire might lead to different iterations of attraction (spooky chemistry, indeed).

On a different register, love might provide a helpful metaphor. There are many forms of love: eros (romantic love), agape (generalized non-romantic love), philia (brotherly love), etc., which have underlying similarities but are felt differently and have unique characteristics.

Attraction is similarly diverse. In addition to the classic romantic and sexual forms, we have other types that variously overlap with and diverge from those two. For example, to make the (arguably) dubious gesture of deferring to the anecdotal, it can be easy to think of a distinctive form of asexual attraction that isn’t romantic per se but has a vividness or vitality distinct from other types of friendship.

This line of thinking might provide an additional answer to the ones given during the Aciman Q & A mentioned above. More specifically, another explanation for why his work can so powerfully capture relationships with which he’s had no personal experience might be because he’s documenting types of attraction that are as varied as are our desires. Attraction pulls on us in all manner of ways, and the ability to capture those can give art unique resonance regardless of the author’s lifestyle.

Unsettling Settled Contingencies: Notes on the Enduring ‘80s

Part of being human is coming to recognize your most fundamental lived assumptions as just that—assumptions. Contingencies that seem like they couldn’t have gone any other way. Good luck shirking that one. The alchemy of time inevitably changes things around you, revealing what had seemed immutable as transitory and what had seemed over as far from it.

This occurred to me while watching the Andy Warhol Diaries. As noted in one episode, Warhol was characteristically insightful in picking up on the vibrancy of ‘80s cultural innovations at a time when their salience often didn’t register for his contemporaries. He was right. The late ‘70s and ‘80s gave us innovations that have shaped the world since, including punk, graffiti, metal, and the like, but perhaps most notably hip hop, which has defined not only the aesthetics of the global cultural landscape but also the conversations around race, police violence, and inequality that define our time. I took all of that for granted when I was growing up. It was the weirdest thing in the world to later realize how young those cultural currents had been when I first experienced them in the ‘90s. If they’d been people, they wouldn’t have been old enough to drink in a bar.

If the ‘80s can be used as shorthand for what those raised in the ‘90s took for granted, then 9/11 can be used as shorthand for the first major cultural rupture that members of that generation experienced first-hand. Bret Easton Ellis is on to something when pointing to a shift from Empire to post-Empire culture in the early ‘00s. The Empire era was that of America after WWII, when the country was on its ascendancy. The Empire perspective was about a polished image and glamor. A public facade. It was Hollywood and formal political speeches. The Post-Empire era has been America after 9/11, when the country has been descending. It’s about undoing that professional/public façade. It’s social media and pajamas in the workplace. Face tattoos.

The Post-Empire flattening of those distinctions brings to mind the passages in Gravity’s Rainbow where Pynchon points out that everyone forgot about the moral and religious basis of the Smithian unseen hand of the market, missing the point and cherry-picking parts of the metaphor. Similarly, Post-Empire culture feels like the ostensibly egalitarian responses of the ‘60s to bubble gum, blue jeans, and the Beatles but without the democratizing veneer. Both trends feel like senseless and disingenuous cases of leveling-down.

Anyway, for those of us on the receiving end of all this in the ‘00s, we could still smell the Empire era in the hallways, but it was clear things were going in another direction. Bunuel’s sendups of middle-class morality felt like dispatches from another world, though we were close enough to the Empire era to have a sense of the bite behind them. Published at the time (2004), sociologist Michael Mann’s Incoherent Empire seemed to put its finger on how American imperialism had lost its composure when faced with its descent. The Post-Empire reality felt as discernible in War in Iraq idiocy as the cultural corollaries described by Ellis.

If 9/11 points to the first rupture, then Covid is good shorthand for the second. Of course, as with 9/11, its elements (social media, Trumpism, etc.) predate the actual event. Indeed, appropriately, that prophet of American culture Iggy Pop rightly put his finger on the atmosphere of the time in the rant that ends his outstanding Post Pop Depressionfrom 2016 (while Dylan might be the genius of looking backward to mine American culture for enduring truths, lowly James Osterberg remains the authority of reading the present and leading the vanguard). This was the start of the conspicuously not-new as the new “new,” or as Pop says in his rant, “There's nothing awesome here [America] … nothing new.”

Indeed, nothing new. From another vantage point, the taken-for-granted impact of the ‘80s on the present has rightly led some commentators to point out that the current time could be thought of as the “Forty-fourth(ish)” year of the Reagan administration. Reagan-era conservativism continues to have an outsized influence on what we take for granted: “family values,” Latin American intervention, nuclear proliferation, etc. On this account, this ‘80s political framework would then have been channeled through the trappings of Post-Empire decline during the 9/11 period to bring us to where we are now. This would be another—quite different—way that the thinking of that time has stuck with us. Could be.

Of course, you could argue that the era of Post-Empire Reaganism isn’t just old wine in new bottles. It’s surely as new as it is old. Or, alternatively, you could go back further and argue that what’s below the surface of this more contemporary American garb stems from uncertainty regarding modernity in response to the horrors of WWI, or follow some postcolonial theorists to point to the collapse of universalizing Enlightenment rationality as the impetus behind all of this. I’m inclined to think there’s at least some truth to all of those perspectives given the accretive quality of history; none of this ever comes from a vacuum.

Still, regardless of where you put the marker of potential antecedents, the point regarding this version of Post-Empire reality is that substantive conceptual innovation has been cut short while the pace of cosmetic change has accelerated, leading to frenetic turnover within stagnant frameworks. This is Pop’s “nothing new” tedium coexisting with the endless succession of “unprecedented times” we’re all so sick of. As something of a metaphor, what comes to mind are the passages in the preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit where Hegel rants about mathematics as unable to capture qualitative conceptual transformation as it is limited to measurement of what appears before it. Similarly, we’re experiencing quantitative change at a lunatic pace amidst conceptual dark ages.

Time unsettles settled contingencies. And, in doing so, it has a way of underscoring that what had seemed settled might have been less so than one had hoped.

The Loquacious Art

Graffiti is a loquacious art. Even better, we can swap the indefinite for the definite article and call it the loquacious art. It is the art of the blurt.

I’ve been thinking about that idea and the nature of graffiti more generally since finishing a post about a stencil I’d seen in a Bogota park. I used the post to riff on the stencil’s themes, but writing it got me thinking about graffiti as a medium, its properties and specificities.

The stencil that was the subject of the previous post. Picture property of the author.

Street art is visual but also intensely verbal. In some cases, it’s literally just words scrawled in public places. In others, it’s stylized depictions of words. Of course, it can and often does include visual depictions of all sorts. Regardless, graffiti is about saying something. It’s a conversational volley.

Spawn mural by the MHC crew (Bogota). Photo taken by the author.

Other styles of art do other things through other means, such as modify sound or craft narratives to trigger emotion, simulate experience, or generate immersive dream states (John Gardner’s “fictive dream”). Graffiti might also do some of those things, but it does them while being fundamentally dialogical. It’s chatty.

What is being said? On one level, street art is a chance to speak back to the city. It’s a vehicle for commentary. This social function of graffiti is what led Jello Biafra to suggest in a spoken word piece that subways and buses be covered in replaceable Kevlar to encourage people to write on the walls.

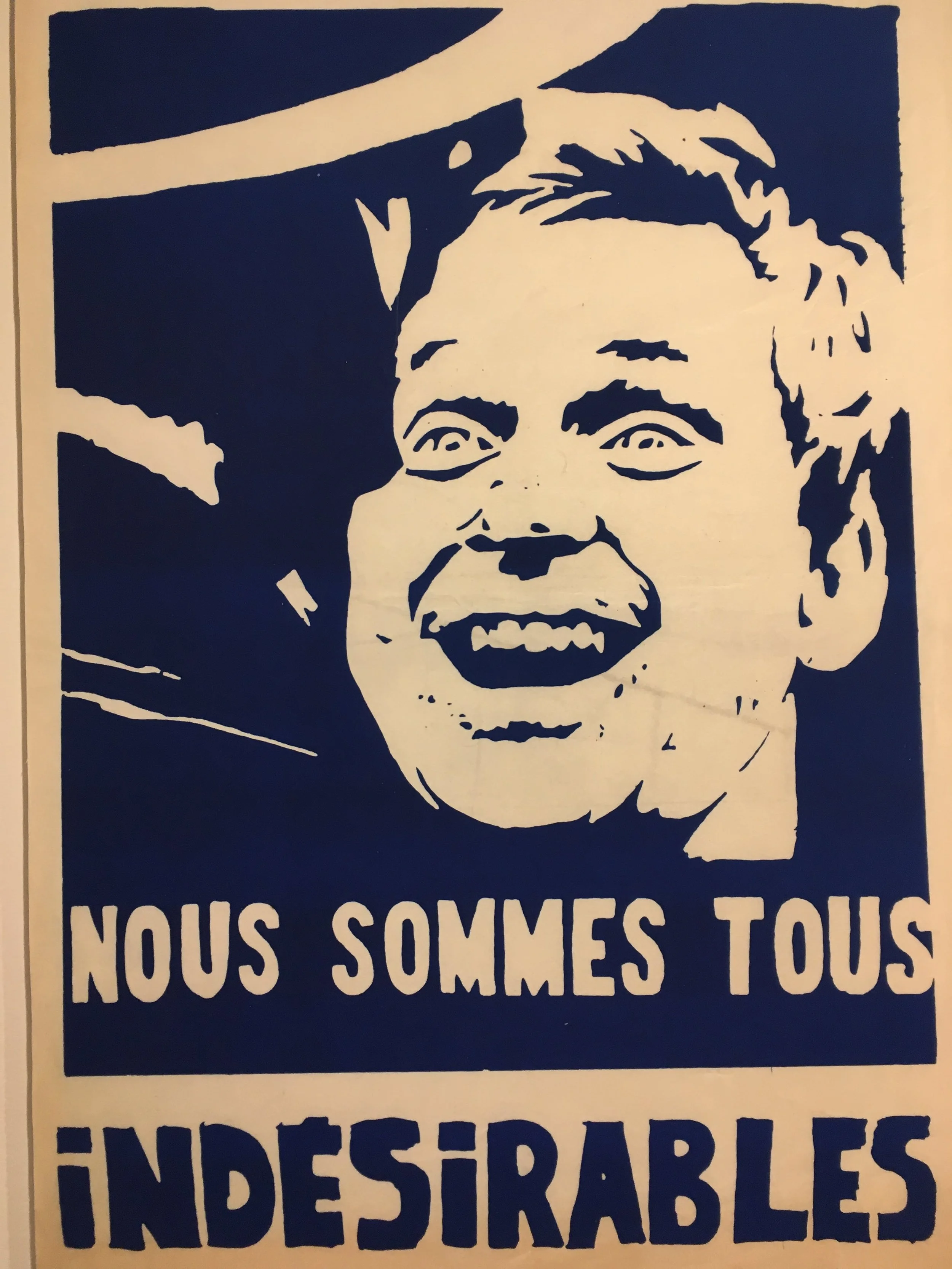

Original graffiti from the May ‘68 protests in France. Photo taken by the author at the Occupying Paris: May 1968 and the Spaces of Protest exhibit

In the case of the Cronenberg stencil, the comment is about the historical, geopolitical conditions that have shaped the world in which we find ourselves. As Burroughs said of the title Naked Lunch to which the stencil alludes, the naked lunch is the “frozen moment when everyone sees what is at the end of every fork.”

Street art might be speaking back, but who is it speaking to? A first answer follows from above: the generalized mass of the city, which is kind of everyone and kind of no one due to the spookily synergistic quality of human sociality. A second is people who get it. Often this is other graffiti writers and their complex culture of codes, shout outs, and crews. But that’s not always the case. The Cronenberg stencil, for instance, has the winking insider quality of pop art freakdom like They Live (1988) and is thus a nod to those in the know.

They Live (1988) stencil produced by some very talented artist (Boston). Photo property of the author.

Who is speaking? Graffiti is an inherently anonymous address. Part of this follows from the illicit nature of the medium. Even if you recognize or know the identity behind the author’s tag, it’s not publicly traceable. In that way, it has little in common with an op-ed signed by the author, though both are a way of chiming in and saying your piece.

The anonymized feature of graffiti’s address is what gives it the impression of being part of a conversation that is always already underway. At its best, this can give graffiti a generative, provocative quality. In his “Masked Philosopher” interview, Foucault famously said, “A name makes reading too easy.” Street art might be the medium of the masked social commentator.

“Wake up Punx” mural by Toxicomano (Bogota). Picture by the author.

To be human is to find oneself thrown into a world of things in general that are always already taking place. Perhaps, in that way, street art can be seen to give physical form to the conversations in which we wake to find ourselves always inevitably enmeshed.

Find an Interzone, Find Yourself an Interzone to Live in

I saw this graffiti stencil in a park in Bogota:

It’s a nod to David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, a cinematic tribute to William Burroughs’s novel of the same name. Cronenberg’s version is a mash up of Burroughs’s works and autobiography that is more about the writing of the novel than the novel itself. Here’s the original monster, the Mugwump, from the film:

The Mugwump is something of a mascot of the Interzone, a figurative city Cronenberg adopts from the novel to stand in for the life Burroughs created for himself as a writer and queer man. The Interzone is a literal city in the film that serves as a metaphor for the psychological places and lifestyle choices Burroughs made as he worked out his sexual and creative desires. The Interzone is depicted as a surreal shadow city of doubling and rot, populated by doppelgangers and telekinetic conversations, where subconscious desires surface and bits of discarded drug paraphernalia are transmuted into writing implements.

The Interzone might be a metaphorical city, but it’s a city—a place we live. The places we live can tell us a lot about the types of beings we are. How we design our human nests reflects the nature of our bodies, our societies, our inner worlds. David Byrne of Talking Heads fame nicely captures this in Bicycle Diaries:

Cities are physical manifestations of our deepest beliefs and our often unconscious thoughts … you don’t need CAT scans and cultural anthropologists to show you what’s going on inside the human mind; its inner works are manifested in three-dimensions, all around us … Riding a bike through all of this [urban settings] is like navigating the collective neural networks of some vast global mind … A Fantastic Voyage but without the cheesy special effects.

Cities are our attempt to change the physical world to suit our inner worlds. In this way, they reflect the stuff of our subjectivity, how our minds work. Byrne considers this on a macro, cultural level, describing the bike ride dérive as a way to explore the “collective mind” of a society.

In that passage, Byrne’s spec lit allusion is to Fantastic Voyage and not Naked Lunch, though the cheesy sci-fi movie to come to mind for me in this case is Forbidden Planet because that one is about how suppressed desires can puncture the rational façade of modernism. Indeed, implicit in Cronenberg’s hallucinatory metaphors is a critique of bourgeois conformity, hypocrisy, and repression, particularly of homosexuality. This can take on tedious undertones of misogyny and juvenile self-indulgence, as we all know was often the case with the Beats and is no more interesting or excusable for being widely acknowledged as such.

In one scene, a character describes the Interzone as a “boil on the underbelly of the West.” In the film, Burroughs’s sexual identity and general outsiderism force him to build his new universe in this underbelly of Western modernity. The stencil points out that people in the Global South may be forced into oppressive urban settings by virtue of the extractive practices of imperialism and the racialized ideologies of colonialism woven into our conception of the human—that is, modernism’s uninterrogated answer to the question we are using cities to consider (viz., the types of beings we are).

On this application of the film’s central metaphor, the Interzone is the physical instantiation of modern society’s attempt to compartmentalize our covert desires, the parts of the psyche, the parts of the system—and thus the parts of the global “city”—unacknowledged. It’s akin to how the kinda sorta sanctioned illegalities of the black market serve the desires that the market will satisfy but the culture ostensibly disowns.

If we were so inclined, we could reverse our approach and come at this investigation from the bottom up by starting with an individual object rather than Byrne’s “collective mind” of the whole of the city. Heidegger famously notes in Being and Time how a tool implies a network of linked purposes and meanings. It makes no sense, for example, to think of a pen in an empty universe; rather, the fact of a pen implies paper, desks, a desire to communicate with other people—the existence of other people to communicate with in the first place. Tools point beyond themselves, giving us clues about the minds that designed them.

The point could be made, for example, that the telephone pole reflects the triumph of our desire to be social over the constraints of physical distance. On the other hand, essayist Eula Biss traces the history of the telephone poll in American society as a tool for lynching. From both standpoints, the telephone poll tells us a lot about the types of beings we are and what we want. The park where I found the stencil has hosted an off-and-on-again protest encampment of displaced indigenous Colombians for the last while.

While Byrne might be right that we don’t need an anthropologist to see the city this way, we do need an anthropologist’s perspective. Even social scientists don’t experience the city as an object of contemplation in their day-to-day lives. For them as for all of us, the city is a collection of taken-for-granted tools until something shakes them out of their quotidian perceptual haze. That’s when anthropologists start thinking anthropologically.

Something has to knock us out of our daily perspective to step back and reflect on our hives from the detached viewpoint of the scientist, as the bicycle helps Byrne do in Bicycle Diaries. Heidegger says it’s when a tool breaks that we stop to think about it as an object.

Maybe street art can still be like the broken tool in Heidegger’s workshop, jostling us out of the everyday to confront the unacknowledged desires behind the worlds we’ve built. Maybe not. Plenty of things are broken.

Slightly but Marvelously Off

While it’s been a brutally hot New England summer in the physical world that we all inhabit, I’ve been in what writer Jami Attenberg calls the “winter” of my inner world that only I inhabit. In 1000 Words, Attenberg uses the seasons as a metaphor for the different phases of the writer’s creative life. As she describes it, spring is about prepping projects, summer is about producing new work, fall is time for rest, and winter is about asking broad questions regarding our creative aims.

My writer’s winter hasn’t done much to help with New England’s crippling humidity this year, but it has helped me to think about method. More specifically, I’ve been thinking about the uses of experimental fiction techniques: postmodernism, absurdism, and the like. I’ve gotten curious about works that include just a hint of the experimental—what we might call a “tincture of the surreal,” or the inclusion of subtle, almost sub-perceptual experimental flavoring in an otherwise realist work. I think of it as the avant-garde literary equivalent of psychedelic microdosing.

What does this approach include? Well, it obviously excludes the absurdism of Beckett or Barthelme, the lush extravagances of magical realism, or the inventions of fabulists like Stanislaw Lem. Great as they are, there is more than a tincture of the surreal in those works—they’re full-blown trips rather than barely perceptible microdoses.

Lynch and the Image

Would David Lynch qualify? On a first pass, of course not. His films certainly have more than a hint of the avant-garde in them. There is, however, a resonance between our idea of the tincture and some accounts of his work. For example, David Foster Wallace’s “David Lynch Keeps his Head” (1995) famously defines “Lynchianism” as the “irony of the banal” achieved through scenes that juxtapose the extreme macabre with the extreme mundane to illustrate how the mundane houses the dark (161). This effect is achieved through shots that DFW describes as “just slightly but marvelously off” (200). As an example of Lynchian logic in action, he gives the charming example of Jeffrey Dahmer putting a decapitated head next to a carton of milk in his refrigerator (161). In another case, he identifies Lynchian elements in Tarantino’s early films, such as Reservoir Dogs, in their pairing of inane small talk with extreme violence (164).

What stands out to me in this reading of Lynchian methodology is the centrality of the image. On this definition, the images are what do the work. Indeed, a case could be made that, on this account, Lynchian surrealism is “thick” in the sense of having an argument woven into its method: by establishing a disjuncture between the expected meanings of two images (hence the “irony”), a point is made about the specific relationship between depravity and mundanity. DFW goes a little further in locating that relationship in the “dark” dimensions of the unconscious in general and American culture in particular (what he calls how “the U.S. present” feels on one’s “nerve endings” (200)). Or both, I guess.

I see the truth in both of its apparent applications. It's interesting, however, to think about what DFW’s rendering of Lynchian cinematic logic might look like if deployed toward other ends. I guess this would be something achieved through the ironic pairing of contrasting images that don’t gesture quite so directly to the dark mechanics of the unconscious and/or relatively recent American culture. As he suggests in that essay, what stood out to DFW about Lynch is how films like Blue Velvet used avant-garde methods to say things that seemed true and authentic rather than trivially clever and self-indulgent. It’s an open question how much those successes can be attributed to the definition of Lynchianism given above rather than the more general surrealism and dream logic of much of Lynch’s stuff. If you stop to think about it, Lynch had a broad aesthetic signature that included distinctive auditory and narrative elements just as much as ironic visual ones.

Anyway, I like all of that about Lynch, too, but what’s stood out to me more recently in reading Ben Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet or Rivka Galchen’s Atmospheric Disturbances is their use of experimental methods to communicate truths about emotional commitment, love, and sacrifice. These warmer truths of the heart are a striking contrast to the points entailed by the thick definition of Lynchianism given above, with all of its underlying darkness. They are a long way from the nearly sociopathic coldness and hermeticism of Lynch’s films. Marcus’s The Flame Alphabet in particular includes Lynchian aesthetics (in the broader sense), which might signal ways of using Lynchian storytelling logic and/or aesthetics to achieve a hint of the surreal being put toward other thematic ends.

Who knows, but the point for now is that some renderings of Lynch’s work seem to be in line with our thinking of the tincture of the surreal, and those definitions privilege the image.

PKD, Lethem, and Plot

Perhaps a more direct case of realist fiction that contains a hint of the surreal comes from one of the masters of speculative surrealism: the mighty Philip K. Dick himself. There were of course many PKDs: PKD the SF pulpist, the philosopher, the religious explorer, the 1960s iconoclast, and the social critic/prognosticator among them. His prescience in predicting so much of modern dystopia is no small part of why he is having something of a moment, as expressed by a recent cartoon in The New Yorker. That fame is deserved: the man’s work is the epitome of capturing how the “U.S. present feels on one’s nerve endings.”

Famously, PKD aspired to have “realist novelist” rank among his many identities, which he achieved to a moderate degree by the end of his life. Of the various PKDs, that’s the one that comes to me now. I’m not the first to point out that even in his more realist, mainstream stuff, PKD is often slightly but indeed marvelously off. Confessions of a Crap Artist, for example, gives us a type of surreal Cheeverism, and only one reason for this is its awkwardly deployed cult and UFO subplot (fumbled, in my view, at the end). As another example, much later in PKD’s oeuvre, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer contains just the faintest hint of a ghost story in an otherwise realist book based on Episcopal bishop James Pike’s life.

I’ve always wondered to what degree PKD included those elements for literary purposes. It might have been intentional. It also might have been that he was so ensconced in spec lit norms that they inflected his realist fiction on reflex. Or maybe he was just a weird guy who couldn’t keep his weirdness out of his writing. Regardless, I for one have always wished he’d drawn those elements out just a bit more than he did. Not everyone agrees, but they feel more like missed opportunities than missteps to me.

I’m not alone. If there’s any writer who took notes when reading his PKD, it is Jonathan Lethem, and that element of the realist works certainly wasn’t lost on him. Lethem works that into his plots to marvelous effect. While the obvious touchstone here might be Fortress of Solitude, with its genre-busting use of an invisibility ring interrupting its realism, I would direct us more to his underappreciated Gambler’s Anatomy, The Arrest, or You Don’t Love Me Yet. Dissident Gardens, arguably Lethem’s most “realist” work would also qualify, as would something like Chronic City, but that one is pretty surreal overall.

Lethem’s more realist works often contain just a light flavoring of weird plot devices (supercars, stolen kangaroos, sex scenes featuring Abraham Lincoln, etc.). Like PKD, Lethem arguably achieves that tincture of the surreal primarily through plot than image (at least in the sense of Lynchianism from above). Often pigeonholed as a “genre buster,” really the mash-up of genre conventions is only one way he achieves that effect, though it is satisfying when the Pynchian comic book qualities of Gun, with Occasional Music surface in his realist prose.

Much remains to be said, but the point for our purposes is that folks like Lethem and PKD largely achieve their hint of the surreal through plot rather than imagery in the manner of Lynch, which signals a second way that a tincture of the surreal can be injected into realist works or scenes.

Almodovar and Texture

So, we’ve got a hint of the surreal achieved through imagery and a hint of the surreal through plot. People also achieve that effect through texture and voice. For example, a synopsis of Almodovar’s Room Next Door needn’t mention anything surreal or strange: two old friends go to upstate New York. One is suffering from terminal cancer and wants to commit voluntary suicide, and the other has agreed to help despite her initial misgivings and discomfort with death. In a sense, nothing weird happens: an old flame surfaces. The police are a little suspicious. No Lynchian severed heads or Lethemian pilfered kangaroos in sight.

But it’s a bizarre, unnerving film. In this case, everything feels just slightly off, but in a way far subtler than in Lynch. A few factors contribute to this: one is the film’s straightforward but odd, distilled visual aesthetic. Another is its restraint and texture. As I experienced it, the film consistently edges up to what seems to be a likely conclusion or turn of events without pulling the trigger. It systematically and routinely flouts Chekhov’s famous principle that “One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off,” or, in other words, that a story shouldn’t plant irrelevant plot devices that have no payoff. Almodovar’s film loads us down with Chekhovian guns, and none of them go off. The result is that the viewer is always a little uncomfortable while waiting for the other shoe to drop. Eventually, so many potential threads are left hanging that the filmic experience becomes unnerving in a way that’s hard to pin down, and even the film’s clumsy lobbying for assisted suicide detracts only slightly from this effect.

Maybe I’m giving Almodovar too much credit on this one, but I’m inclined to think he did that intentionally. Regardless, for our purposes, what matters is that this reading of the film indicates a third way that a largely realist work can host a hint of the surreal viz., vibe and restraint. Whether one sees it in Almodovar specifically or not, such an approach could be redeployed elsewhere.

Why Bother with Just a Hint?

A simple question: why bother? Whether done through imagery, plot, or voice, what is to be gained from such an approach? To return to DFW on Lynch, I don’t know that I would say it communicates how the U.S. present in particular feels on my nerve endings. I wish we lived in an era that had only a “hint” of anything in our tawdry, grandiose dystopian present.

With that said, I do think the truths that such a method can communicate go deeper than simple cleverness or cool storytelling, though they’re great for being clever and telling cool stories. Sticking with contemporary spec lit examples, one thing I like about Paul Tremblay’s A Head Full of Ghosts is how it addresses noisy, discordant lunacy in ways that are ultimately amenable to rational explanation. Without making potential possession or ghostly inhabitation subtle in the least, the book always offers a potential way out through recourse to physical explanation. That’s probably how I would experience a horror-film scenario if it were to happen in my life. But horror-film experiences, or freakouts like those in PKD’s Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, don’t happen in my world. This isn’t to say I don’t adore art that expresses those truths, but they don’t capture much of how life feels on my nerve endings (which, to be clear, isn’t to say either I or the author want that of them).

A tincture of the surreal does, however, capture how life feels to me. Everyday reality often feels a little flat with just an echo of something more. It has a certain squinting, was-that-it? quality. Large parts of life take a faint otherworldly tint such as in Almodovar’s film or a vague echo of something weird in the manner of PKD’s Transmigration. In a different way, Lynch’s imagistic surrealism does reflect how my unconscious feels, but that dream logic is so divorced from my daily waking experience that I think I get something different from his stuff.

The tincture of the surreal captures something of how life feels and might reflect nostalgia for a time when life was less tediously overblown that one could think of the present as indicating just a hint of something being off. For those reasons and more, such a tincture is, indeed, marvelously but slightly not off.

What Makes Art “Left Wing”?

I recently listened to Ross Douthat’s interview with the screen writer Tony Gilroy. The central question was whether Andor is a “left-wing” show, and more generally, the connection between art, politics, and ideology. It was a fascinating discussion. I’m hesitant to chime in too much because I’ve never watched Andor (I’m so out of the loop I hadn’t heard of it before listening to the interview). Nevertheless, the discussion got a little muddled, so I thought I would sharpen two distinctions made in the interview.

Gilroy took issue with Douthat’s claim that Andor is a “left-wing” show. He was even less patient with the idea that Michael Clayton was a “left-wing” movie. As I understood it, his argument was that the show was not political (or more specifically “left wing”) because it does not set forward policy positions or a blueprint for social change. Gilroy called himself a “moralist” focused on interpersonal relationships and character. On his account, for his work to succeed as art, he must have empathy for all his characters and give each a fair shake.

Douthat, for his part, agreed that this empathy was central to making good art, and he commended Gilroy for producing art that meets that standard. However, he felt that this didn’t prevent the show from setting forward an implicit ideology. On Douthat’s account, by leading us to root for revolutionary forces against a fascistic dictatorship, Andor communicates a left-wing perspective about social change and progress.

To Gilroy, in contrast, a person of any political ideology can be comfortable with the perspective he puts forward in Andor because his primary point is moral and focused on the at least ostensibly apolitical question of community. He makes a similar point about another of his works, Michael Clayton, which apparently has a pesticide company that has knowingly polluted a small town as its central antagonist. On this rendering, the film is less an objection to capitalism than a condemnation of immoral or misguided behavior (after all, who of any political ideology would root for a company that so clearly prioritizes profit over the health of the community).

Part of the confusion here might have to do with how we’re thinking about the term “politics.” Both thinkers agreed that the issue wasn’t about politics in the sense of specific candidates, campaigns, or platforms. As an entry in the Star Wars franchise, it would be a bit of a reach for Andor to attempt that.

Without saying it directly, Douthat seemed to be thinking of politics in a broader sense of underlying beliefs and assumptions that inform a socio-political worldview, arguing that Andor is political in this broader sense (perhaps “political but not of politics” as Adorno says in Aesthetic Theory). This is about one’s underlying vantage point regarding social progress, societal change, political violence, and the like.

Indeed, at least in the context of this discussion, a case could be made for there being at least three strata of abstraction in political thinking. All three have both characteristically left-wing and right-wing positions. The first, level one, would be broad ideologies regarding the good life and paths to the good life. The second, level two, would be the mid-level ideologies or quasi-ideologies that are the domain of the rival camps in contemporary American politics (“wokism,” “Trumpism,” etc.). Finally, a third stratum, level three, relates to specific policy issues or candidates.

To return to the show, it might be that Andor is political in the broadest sense of indicating general commitments about how to organize a way of life (level one) but not in the other more “applied” regards (levels two and three). Part of the confusion in the discussion might have then been because Douthat seemed to be thinking of something closer to level one while Gilroy was thinking of something closer to level two.

Furthermore, Douthat pointed out a second important consideration: the artist’s choice of villain or protagonist will inevitably express a broader idea than the characters themselves. On the one hand, Gilroy’s point stands that his aim is to cultivate empathy. On the other hand, fiction is about embodied characters in particular settings doing recognizable things. Seen from that perspective, one way to phrase this might be that among the infinite number of people my art could choose to cultivate empathy for (e.g., a middle-class clerk, a 1980s business executive, a struggling factory worker), the fact that I’ve chosen one over another indicates something about how I see the world and what I value--whether consciously intended or not.

This needn’t mean that the artist think that empathy shouldn’t be extended to other people or wouldn’t support art that cultivates empathy for another (perhaps even rival) person or group. Nevertheless, it’s impossible to make art that simultaneously cultivates empathy for all people at one time. The artist has to make choices, and those choices will say something about how they see the world. This might be a second way that Andor gestures toward an implicit political critique.

I’m sure both Gilroy and Douthat would agree that the connection between art and politics goes much deeper than what they had time to address on the podcast or I’ve said here. Hopefully, however, these distinctions help to clarify the stakes of their interesting discussion.

On being an Amateur

A few years back, I put up a post about Philip K. Dick that was my attempt to think through how PKD had come to have a personal significance for me, what that significance was, and, more generally, how and why we invest writers with personal significance in the first place.

Having now finished almost all of the remaining PKD works I hadn’t read up to that point, I find myself thinking back on what might have been going on there. Part of what was at work was the feeling of having been an amateur.

The amateur is a strange role with its own peculiar psychology that reflects distinctive ways of thinking that can be as liberating as constraining. I came to the identity of the amateur naturally and early. As adolescents, I think my friends and I saw ourselves more as novice, informal intellectuals on independent paths than kids who liked to read or even high school/future university students. A community of autodidacts inventing core parts of the academy as we went without knowing that they were core parts of the academy. That was weird, but it fit our mistrust of mainstream institutions (the school in particular), punk rock DIY ethos, and blue-collar provinciality.

This was fed by the fact that a lot of what interested us wasn’t taught in school—at least not our school. That’s obviously true of every kid, but an added twist here was that a lot of that material was academic—philosophy in particular, but huge parts of the humanities and social sciences—which fostered confusion in us about what it meant for something to be “academic.” The internet hadn’t exploded yet, and our parents hadn’t been to college. We were weirdos picking through used book sales and public libraries, and on some level, I think we thought scholarly behemoths like Chomsky or BF Skinner or C. Wright Mills or whomever were the same. Of course, it seems impossible now not to think of them in lavish faculty lounges, but that was how things seemed from our distinctive vantage point.

That belief died a natural death when we graduated. Arriving at college, we were suddenly thrust into a well-defined universe of experts who’d studied those things for years with systematicity and resources we couldn’t have imagined.

The experience was exciting, jarring, and humiliating. There were advantages to having started as amateurs: we brought a lot of passion and authenticity to what we did, and we had developed tastes (albeit idiosyncratic ones). We were limited to what we were able to find, which meant we often started with minor, obscure works rather than major canonical ones (Sartre’s out-of-print reflections on the Cuban revolution but not Nausea). This led to unusual but sometimes interesting emphases turning up in our thought.

In hindsight, I fell for PKD during this period because I was an amateur taken in by his snazzy thought experiments questioning the nature of reality and because I recognized him as a fellow amateur taken in by snazzy thought experiments questioning the nature of reality. His writing has a late-night bull session feel that mirrored what our lives felt like, which might be most directly dramatized in places like A Scanner Darkly, though animates all of his work. I’m far from the first to point out that PKD is the patron saint of the counter-culture humanistic amateur.

The amateur works in a very different way from the expert: more experiential, eclectic, and oriented toward the particular. There’s beauty and power in that authenticity. It can be liberating. At the same time, it can be alienating and constraining. In PKD’s case, his amateurism led to authenticity that resonates with readers even today, and I suspect at least up to a point that is what made his work innovative and visionary. At the same time, it hobbled his prose and thinking. Professions can have blind spots that hinder innovation, but more often than not, the professional does it better, avoiding well-recognized missteps and common errors.

For all his paranoia and cynicism, PKD seems to have had his own ambivalence toward expertise. In a podcast interview, one of his ex-wives, Tessa Dick, mentioned that he dreamed of turning the manic, amphetamine-fueled ravings of his Exegesis into a legitimate philosophical publication and was concerned that it wouldn’t be taken seriously by professional theologians.

Understandable as it is, a part of me hates to hear that. On one level, I like the idea of the Exegesis as the work of an outsider artist’s mind on fire. Yet, another part of me would like to see its rough edges smoothed out by an expert.

I still struggle with where I fall on that, as well as with the attendant social class anxieties bound up with professionalism that have been so brilliantly explicated by Dewey, Ranciere, and many others. Some days, I cheer the technocrat and some days the ignorant schoolmaster. Much like PKD himself, I suppose.

No Wave, Performance, and the Frenetic Flux of the Unchanging Present

My candidate for the least-striking observation of the day: “authenticity” is a preoccupation of the zeitgeist. The term is bandied about constantly, which is understandable because we’re all fed a lot of bullshit. But I’ve been wondering if authenticity’s neglected counterpart, performance, might not have greater utility for our end-of-days present.

It would be boring to point out that separating authenticity from performance is impossible. We’ve all got our Nietzsches, Freuds, and Sartres at the ready to point out that humans are odd creatures that put on a show for ourselves as much as for others. For my money, sociologist Erving Goffman’s brilliant and hilarious The Presentation of Self in Everyday Lifestands out, though David Grazian’s classic Blue Chicago about how blues performers engineer the impression of an “authentic” performance is just as fun on a different register.

What does it mean to “perform”? A rigorous definition could be derived from Goffman, yes, but countless others as well--Homi Bhabha’s account of mimicry in The Location of Culture, the existentialists, etc. It’s enough for now to say that it has much to do with self-consciously harnessing the inherently performative dimension of social life. If to be human is to manage one’s self-presentation, then consciously steering that performance for reasons beyond those of standard social decorum would lead to the type of performance we have in mind here.

Such as what reasons? Well, regardless of its necessity, performance can enrich experience. I have a soft spot for that pleasure. When critics call something “pretentious,” it’s often a cue I’ll like it, which might have something to do with having grown up in a rural area in which not embellishing at least a bit meant things were going to be pretty bland. More to the point, while there is necessity and pleasure in performance, there’s also utility. Performance can be a means for underscoring unappreciated truths or facets of lived reality.

I’ve been thinking about this recently in terms of No Wave film and punk rock, which are as overtly performative as anything I could imagine. Few things are more self-consciously contrived than the deliberate transgression of social norms in the tit-for-tat terms of punk. On an interpersonal level, punks themselves are often irritatingly histrionic.

Obviously, there is a point behind the comic theatricality of the “loud, loud, proud and punk” performance. At this point, that might not be a particularly original point, but it’s worth asking if it’s relevant and what its effects have been or could be.

It cuts both ways. On the one hand, in its day, the crass and willfully offensive edges of what we know as punk highlighted that many social conventions are arbitrary, hypocritical, and oppressive. In a Bourdieusian sense, a lot of social norms and aesthetic attitudes are vehicles for perpetuating social inequality. No doubt.

On the other hand, a part of me wonders if that performance didn’t help to usher in, or at least reflect, our current shameless social era. As fun as it is to beat up on the squares, I wouldn’t be the first to point out that the logical endpoint of a lot of that strategic offensiveness is reactionary hate and willful stupidity.

But that’s only one side of the story. I’ve been working through some of the classics of No Wave and the Cinema of Transgression over the last few months, which are of course punk’s filmic fellow travelers. Appropriately, they’re often just as intolerable aesthetically as many of their musical counterparts. It’s nice they’re out there, but, man, they can be tough to get through.

Still, what stands out to me is how timely Cinema of Transgression/No Wave’s underlying thrust is even while its trappings might seem a little dated. Of course, the shock value of getting high, saying crazy things, having sex, and speculating on government conspiracies has long since worn off.

Yet, many of the tradition’s points about sexuality, gender, and other oppressive norms might be more relevant than ever. As I’ve worked through them, I almost can’t believe how contemporary many of Nick Zedd, Lydia Lunch, Richard Kern, et al.’s points remain.

The films feel both tremendously contemporary and a little dated. Then again, maybe those dated features aren’t so dated if they’re inextricably linked to the broader conceptual critiques of hot-button socio-cultural issues? It’s unclear. The frenetic flux of our unchanging present where everything is new while fundamentally remaining the same blurs the relevant and the irrelevant.

We are experiencing rapid cultural change characteristic of a new post-Empire era (the terms of which punk may have been an unfortunate harbinger). Yet, it’s all as old as it is new. In many ways, the social categories and terms with which we make sense of our experience are fundamentally the same as those from the 1940s and 1950s. The modern culture wars feel like an eerie recasting of the Red Scare and monochromatic homophobia from times before. The template for our socio-cultural understanding was set nearly a century ago, and it still provides us with the categories with which we make sense of the world. This is all happening in the midst of everything being whipped up into a lunatic cyclone as the culture tanks and the nation declines.

Part of the challenge of the moment is to sort through this blurred relevance/irrelevance and break our stalled social progression. Do we continue to search the horizon for the vanishingly distant possibility of something new? Or draw upon the muted threads of counter thrusts that were both absorbed and not? Both? If so, which ones tighten the knot and which ones loosen it?

In his Cinema of Transgression Manifesto, Zedd wrote of the movement: “There will be blood, shame, pain and ecstasy, the likes of which no one has yet imagined.” The problem might be that we have yet to have imagined. Or maybe the problem is that we have.

Paradoxes of Place and Habits of Mind

There are the technical paradoxes of the philosopher, which aren’t of interest to anyone but the philosopher. There are also, however, “lived” or “relaxed” paradoxes, which aren’t so much paradoxes per se as unexpected twists in the way life tends to work. The former shapes thought; the latter shapes how we shape lives within a world shaped by thought (or from another perspective, not shaped enough by it).

Entrepreneurs like talking about lived paradoxes. For example, they’re often quick to point out that offering fewer services to fewer people leads to more leads. That might not be a paradox per se, but it’s a counter-intuitive outcome insofar as one might reasonably expect that offering more services to more people would lead to more business.

Another example of this type of puzzle, this one from outside the entrepreneurial world, could be called the Big City Paradox. While one might reasonably expect that big cities would encourage diverse, broad, and “big” lives, they often end up yielding surprisingly constrained and predictable lives. Even when living in a metropolis of millions, we often find ourselves doing the same things with the same people in the same places. Part of this is necessitated by structural conditions like the need to work or the expense and inconvenience of commuting in big cities. Another cause is simply how we as humans navigate the world. As Alva Noe points out in Out of Our Heads, even the most freewheeling of us tend to be pretty routine-oriented creatures in the grand scheme of things.

Of course, the Big City Paradox applies to any large, diverse scenario--not just physical settings. The digital world is an obvious example. While the internet theoretically opens the entire world to us, in many ways it’s done more to restrict than broaden our range of experience. More often than not, we end up in algorithmized echo chambers, cycling endlessly through the same sites.

There’s a reverse movement corresponding to the Big City Paradox: we can call it the Small Town Paradox. Rural settings are often thought to foster ignorance and prejudice, and there’s truth to that as far as it goes. At the same time, in a reversal of the Big City Paradox, being in a more parochial setting can foster a type of broad-mindedness.

Let’s start with a metaphor. One way to experience a gallery or art museum is to rush through the rooms, devouring as many distinct works as possible. Another is to focus on just a single work or small number of works. In a sense, the second approach obviously entails reflecting on fewer things, and thus in one regard, it’s a “smaller” experience. Yet, from another standpoint, focusing on just a single work leads to appreciation of that work’s nuance and inner diversity. It can be shocking to see how much you’ve missed in an artwork when you spend an extra few minutes with it—much less hours.

This experience can be forced on you. In a gallery you visit weekly and that only hosts a few key pieces, you likely have no choice but to visit and revisit the same works with ever increasing appreciation for their nuance. By the same token, revisiting a single neighborhood time and again allows for awareness of its inner multiplicities. This isn’t “better” in any sense than a whirligig tour of Paris, but it has its own beauty.

I grew up in a town that had its population counted in thousands if not hundreds. Especially in the pre-internet era, living in a community of just a few thousand people meant you were likely the only person you knew who had your niche interest or skill. On the one hand, this made it hard to find your niche in the first place, and it could be isolating when you did. At the same time, it also meant that you had no choice but to compromise with other people’s tastes and preferences. I was deep into punk rock/hardcore in my early teens, but, for some reason, my friends generally didn’t share my excitement for whatever Man is the Bastard 7” I’d gotten my hands on (this makes more sense to me now). One result was that if I didn’t already have a taste for the Beatnuts or Dream Theatre or whatever, I would have at least the rudiments of one beaten into me through the blunt force of exposure ad nauseum (this was pre-Spotify, so we listened to the same shitty, scratched CDs time and again).

The result was that you were forced to stretch yourself in a way that wouldn’t have been necessary in bigger settings where you could find exactly what you were looking for. The paradox of the entire town being a small, homogeneous clique was that it was too small to accommodate small, homogeneous cliques. There is multiplicity within the uniformity of micro-settings in which everyone does indeed literally know your name. The particular can lead to the universal.

I seem to remember Nietzsche noting somewhere that switching to writing on a typewriter changed how he thought. If I remember right, he meant that more descriptively than evaluatively: this wasn’t for the better or worse. And it was more about how he organized his thought than specific beliefs or conclusions. Similarly, I do wonder to what degree the patterns and shape of my thought can be traced back to my experience with the Small Town Paradox. I’m not thinking of my ethics, aesthetics, or even personality, but rather how I organize my thought—the heuristics and rhythms that structure how I work with ideas.

It's possible that having to stretch myself by virtue of having so little to concentrate on might have trained me to appreciate perspectives that were at least marginally different from my own. By the same token, having so little to focus on meant I had no choice but to learn the ins and outs of the few resources I did. I learned to see the few books in my small personal library from different perspectives and through different lenses. Sometimes I wonder if my tendencies to ferret out detail through close exegetical reading and shift between different theoretical approaches to the same content might flow naturally from having had access to such a constrained swath of material as a kid.

In a somewhat more concrete sense, I would say it encouraged a preoccupation with some of my pet themes, such as the disjuncture between appearance and reality, though I suppose that’s been a central focus of Western thought since at least Socrates’s day, so who knows where I inherited that from. Still, I think it’s one of the reasons I like David Lynch movies, Greil Marcus’s Old, Weird America, Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip, or American vernacular fiction that hints at darkness below a placid social surface. There’s an astounding number of nested social universes within a small town, and many are hideous.

I’m not sure how different any of this would be in a post-internet world. And I certainly wouldn’t have wanted to have lived my whole life that way. It’s just to acknowledge that there can be a kernel of unexpected multiplicity at the heart of stifling uniformity. Ultimately, both have their place: there are times to consume widely and ravenously and times to mindfully foster appreciation for each bite.

Maybe part of what’s at stake is that the Small Town Paradox might be on the edge of extinction. One wonders if it’s taking a certain style of thought with it.

The Paranoid Style in American Ideology

On a first pass, it might seem that paranoia has undergone a distasteful memeification in recent internet history. It doesn’t take much, though, to see that at least in the American context, modern paranoia is old wine in new (digitized) bottles. Indeed, as the mighty Richard Hofstadter noted half a century ago when diagnosing the paranoid style of American political thinking, “American politics has often been an arena for angry minds.” Americans have long been a paranoid people. But what does that mean in today’s terms?

***

Of course, neither Hofstadter nor I are thinking of the clinical form of paranoia. In this, I follow Luigi Zoja in seeing paranoia as a universal style of thought; it’s a manner of thinking. Paranoia is a ditch that all thought can fall into. Of course, that manner of thought can come to constitute (or at least be characteristic of) a psychiatric condition if taken to an extreme. By the same token, depression is a universal human experience, but it can become a psychiatric disorder when prolonged in duration or excessive in intensity. Paranoia is similar in that way.

Just as a tendency toward paranoia can be more or less characteristic of an individual, it can also be more or less characteristic of a society. This is Hofstadter’s point about American political thought. Societies and epochs can encourage universal human traits to greater or lesser degrees, which can lead to a psychiatric outcome on the individual level or the cultural equivalent of a psychiatric outcome at the societal level.

Definitions of paranoia have been largely consistent and intuitive: something along the lines of a “disorder characterized by delusions of persecution or grandeur” will get us in the ballpark. This central thrust doesn’t change much across the definitions given in modern psychiatry or by Jaspers, Freud, etc. More specifically, Zoas gives us the following central characteristics of paranoia: suspicion, persecutory projection, rigidity, megalomania, secrecy, meticulous obsessiveness, etc. (14-16). Again, likely nothing too surprising there for the casual reader.

A key facet of paranoia is its close connection between logic and delusion: paranoiac thinking is based on a single overarching flawed assumption, but it is otherwise internally consistent and rational. That key assumption goes unquestioned, but that’s not because logic is absent—on the contrary, rationality is often hyperactive in paranoiac thinking, though within narrowly constrained bounds and with an irrational core. It’s a bit like Locke’s famous example of a man who mistakenly believed himself to be made of glass (obviously inaccurate) but who was able to properly reason based on that flawed assumption (“It is reasonable for one made of glass to do the following…”).

Paranoia enlists reason to shore up its flawed assumption. It does this in a few ways; one is by clamping down on competing explanations. There’s a fundamental conservatism to paranoia insofar as it resists alternative explanations and silences competing narratives. Part of that is the inevitable result of its myopia, but paranoia also engineers an interpretive inversion. As Zoas puts it, “Thus paranoid interpretation proceeds by accumulation: anything that might contradict it encounters an inverted logic and becomes confirmation … [of its flawed thinking] … once set in train, paranoia is self-nourishing” (10). Put differently, paranoid reasoning frames inconvenient facts in a way consistent with the underlying assumption(s) of the paranoid belief system. What doesn’t fit objectively is made to fit through interpretive legerdemain. This is what leads paranoia to be self-perpetuating or “self-nourishing”: channeling all interpretation through the prism of this central flawed assumption leads every fact, regardless of how inconvenient, to appear like further evidence of the paranoid interpretive framework and thus reaffirm that belief system.

Because paranoia relies on a type of persecution complex, it can be easy to overlook how violent and hostile it can be. Paranoia is an aggressive way of thinking: it assumes enemies and threats, as can be seen in Hofstadter’s example of McCarthyism. In my view, the result is yet another way that paranoid reasoning engenders self-perpetuating circularity: anger-ridden metanarratives can lead one lost in the throes of paranoiad reasoning to lash out at one’s (imagined) enemies, which can in turn lead those victims to engage in retaliatory violence. This violence can make the initial paranoia that kicked off that cycle in the first place appear justified.

Paranoia’s bellicosity combined with its discomfort with competing narratives can lead to struggle regarding messaging and knowledge, encouraging social conflict around definitions, meanings, and interpretations. One can see in paranoid reasoning a stubborn refusal to accept definitional multiplicity in a way that can become violent in its intention to reaffirm simplistic, outdated terms of social relations. This might start with an initial refusal to tolerate competing messaging, followed by a characteristic inversion of facts to reorient them to one’s simplified overarching narrative, which may in its last form become increasingly violent if and when oppressed social groups continue to advocate their perspective, values, or terms of existence.

***

Paranoia’s inverted logic can start to sound a lot like Marx’s camera obscura from The German Ideology. Marx famously uses the camera obscura as a metaphor to explain the concept of ideology (with the term used in a technical sense here). As commentators have pointed out for generations, Marx was never all that clear on exactly what ideology is on his account, and many thinkers have done little to make the problem better. Still, in the classic Marxian version of ideology, the conditions of modern capitalism set in motion a type of confusion whereby the observer comes to misapprehend the terms of material and mental production. The complexities of capitalist production lead people to confuse causes and types; they get them backwards in a way similar to how the mechanics of old cameras would invert an image when capturing it.

Tommy Shelbie provides one of the more useful and systematic reworkings of ideology. In “Ideology, Racism, and Critical Social Theory,” Shelbie defines an ideology as a type of belief system that is (1) widely shared, (2) forms a coherent normative and/or descriptive system of thought, (3) shapes a group’s self-conception and/or normative outlook, and (4) has a significant impact on social action/institutions (158). An ideology is a belief system that is both distorted in a way that reinforces social relations of oppression (172) and whose acceptance can be largely or partially explained by a society’s class-structure (183). Thus, an ideology is not just any form of distorted thinking prompted by any type of confusion. Rather, an ideology is a social belief system that preserves an oppressive social order through distorted/distorting thinking that is reflective of a society’s social hierarchy, which it (the ideology) legitimates (181).

Shelbie’s account is a much more workable definition of ideology than we often get in Marxist commentary, though it’s obviously far from the last word on the topic. Still, it would be a distraction for us to dig into the interminable debates surrounding that hoary concept. A (very) rough sketch is all we need today, and Shelbie’s account nicely provides that.

Ideology obviously isn’t paranoia: an ideology is fundamentally social while a paranoid system need not be (and in its more clinical forms is almost defined by its idiosyncrasies). Furthermore, at least on Zoas’s definition, paranoia is an inherent human trait and thus certainly broader than the social terms of any given ideology, though on some accounts, I suppose the potential for ideological thinking in general could be thought to indicate an underlying universal human trait (similar to the way ideology’s sibling hegemony has undergone so many twists and tweaks that we see it crop up in the most unexpected of places to do the most unexpected of work).

Nevertheless, the overlap between paranoia and ideology is clear: both paranoia and ideology entail distorted thinking that inverts a subject’s understanding of social conditions. Both are about the subject misinterpreting social affairs in such a way as to inaccurately apprehend the nature of the conditions at hand for reasons that are often self-serving or at least undertaken in false consciousness (in the sense given to us by Engels of one adopting a belief without being fully aware of why one is adopting that belief). Both leave unquestioned their fundamental assumption(s) and engage in acts of hermeneutical inversion to substantiate that unquestioned assumption(s) in a way that rests on an irrational core and fosters delusion. Both have a certain conservative thrust in discounting or silencing competing narratives or inconvenient facts (or at least refusing to recognize those facts or narratives on their own terms).

The two concepts have a certain affinity, and we could blend them in various ways. For example, from one vantage point, as Shelbie rightly notes, ideologies are shaped by or draw from the broader cultural repertoire of the society in which they arise. In that sense, one way to understand the relationship between the two is to think of ideology in the American context as drawing on the widespread societal terms of paranoia, which would in turn be an underlying human trait that American society would foster. Depending on how we choose to read that, we could conceive of paranoia as the cultural garb of ideology in this context, or as a constitutive facet of ideology in general, or as a reflection of a distinct variety of ideology regardless of cultural context (i.e., it might be that paranoia is a constitutive of ideology in general—rather than ideology in this particular place and at this particular time).

***

All of this on ideology, hermeneutical conflict, and paranoia brings us to the door of John Carpenter’s They Live(1988). We’re hardly reaching here: They Live is often interpreted as an allegory for ideology, including in Slavoj Zizek’s wonderful reading of the film in The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology. Director John Carpenter has acknowledged the film as a statement on Reaganomics and consumerism.

They Live does not have a complex plot. The film follows protagonist Nada (“nothing”--not the first time the film lays it on a little thick), a homeless drifter played by the wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper. Nada wanders Los Angeles, California, in search of work until finding a stash of sunglasses in an abandoned building. Wearing the sunglasses allows him to see the hidden subliminal messages in modern marketing, as well as perceive the real appearance of the alien elite who in disguised form manage American society. With this knowledge, Nada collaborates with friend Frank Armitage (Keith David) on a quest to spread the truth by publicizing the “true” narrative of alien control and thus freeing the human masses from the servitude in which they unwittingly collaborate.

I’ve always been of two minds about They Live. I love it as a symbol, and I’m as likely as anyone to fetishize its place as a “wink and a nod” gesture in the counter culture. The critique of neoliberalism, consumerism, and 1980s yuppie culture is certainly in line with my own beliefs, and a fair amount of ink has been spilled on unpacking those themes in the film. It has its appeal and a certain unexpected depth. The film is, for example, superbly attuned to the pleasures of ideology. The characters in They Live are as much collaborators with as dupes of ideology. It’s not just that the alien overlords trick them.

Indeed, as Zizek’s quirky Lacanianism rightly points out, the thing about ideology is that it feels good. I would argue much the same could be said of the gentler forms of paranoia, which can serve a certain theodical function of explaining suffering in simplified, narcissistic terms. To return to Hofstadter for a moment, paranoid thinking is generally simpler than reality and often comforting in making the person experiencing it an interesting enough target to warrant the excessive attention and focus of being persecuted. Similarly, They Live links ideology to self-indulgent consumerism, and Zizek’s reading of the film’s hilariously protracted fight sequence in which Nada wrestles his partner when the latter refuses the anti-ideology sunglasses is a potent metaphor for how hard and uncomfortable it can be to leave the delusions of ideology (or, on our account, pop paranoia) behind. It’s a brilliant point.

Still, one wonders if They Live doesn’t provide grist for the ideological mill—in form if not in content. I admit I wasn’t shocked when the film was briefly picked up by modern reactionaries a few years back. This isn’t to say that was Carpenter’s intention—it obviously wasn’t, and people are right to point that out. The film was clearly intended to communicate a critique of unfettered capitalism and hedonistic social conservatism, and it’s certainly on the mark on that point. More specifically, its emphasis on messaging and popular media is arguably more relevant and satisfying in our hyper-technologized era of social media than even at the time of the film’s initial release.

But maybe too satisfying? One wonders if They Live’s celebratory account of a somewhat generic sense of paranoia, willfully cartoonish quality, and self-congratulatory focus on “others” like the (literal) alien might not flirt with the self-indulgent form of paranoia we’ve woven into the American vernacular of childish “fight-the-powerism.” Naturally, we’ve put on the glasses. We know better. We’re the stars of the show. Our bullshit detectors are turned up to 11. All of this can start to sound a lot like the simplified, persecutory thinking of mainstream American paranoid ideology. This would be true regardless of Carpenter’s (laudable) intentions or Zizek’s astute account of the film’s nuanced treatment of ideology.

Then again, in our era of regressive McCarthyism intended to fix meanings through force (one official language, two genders, one triumphant national history, etc.), we do often find ourselves at odds with a clearly identifiable aggressor. Jason Stanley rightly emphasizes the importance of messaging, education, and hermeneutical warfare in fascistic movements—both our own and in general. To return to the point about paranoia’s self-perpetuating bellicosity, dissident signals are indeed being silenced in this crazed modern iteration of the Red Scare.

In that sense, They Live might be the best of all metaphors for our modern ideological era. It’s possible that the film’s mirroring of the structural form of paranoid ideology might be justified precisely because people are acting aggressively based on paranoid ideologies. This isn’t to say we shouldn’t guard against getting too comfortable with such a simplified rendering, but it might make sense to operate at least partially on paranoia’s terms because those are the terms on which other people are acting. There is occasional legitimacy to paranoia when shorn of its ideological excesses precisely because of its ideological excesses.

Notes on John Franklin Bardin: The Politics of Fear, Revisited, Revisited

Writing at the time of the publication of the John Franklin Bardin Omnibus, Greil Marcus lamented in his 1976 piece for the New Yorker, “The Mechanics of Fear,” that Bardin was a forgotten figure of 1940s postwar American noir. In 2006, Jonathan Lethem noted in his introduction to a then-newly released series of Bardin’s works, “The Mechanics of Fear, Revisited,” that decades after Marcus’s piece, Bardin remained unfairly neglected.

Now, nearly twenty years after Lethem, we can say again that Bardin is still underappreciated. The Omnibus is out of print. The gorgeous Centipede Press editions to which Lethem contributed his introduction are out of print. He’s left out of many major studies and is the subject of a strikingly thin scholarly literature. Maybe Bardin is destined to hang on that way—a cult figure lurking at the edges of a certain thread of American critical consciousness.

That is unfortunate, however. Bardin (let’s agree to call him “JFB” like David Foster Wallace is “DFW”) was indeed aesthetically innovative in seeing the artistic potential of vernacular (in this case noir) fiction at a time when such awareness was rare. In that regard, as Lethem notes in his introduction, JFB did indeed lay the groundwork for later figures like David Lynch and Paul Auster.

Beyond his aesthetics, JFB’s thematic work was innovative and is particularly timely. In this mad era, thinking the unthought in his oeuvre can ground us in a distinctly American counter-heritage that provides helpful tools to weather our current, uniquely alienating, epoch.

In that spirit, I recently worked through the three novels in The Omnibus: The Deadly Percheron (1946), The Last of Philip Banter (1947), and Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948). I took much from them because there’s much to be taken from them.

Biographical Note

There’s a certain sequence of notes that commentators on JFB are obliged to hit. We’ve already gotten our first out of the way: he is obscure.

We can now move on to providing the same biographical sketch of JFB that we all give, mostly cribbed from crime writer Julian Symon’s introduction to the Omnibus. Symons’s introduction is quite good in its own right (he interviewed JFB for it), but my sense is there isn’t much else out there anyway.

In short: JFB (1916-1981) was a quirky crime writer born in Cincinnati. Forced to leave college early due to financial difficulties stemming from his mother’s schizophrenic breakdown (a critique of psychiatry and fixation on mental illness runs through his work), he undertook an extended course of self-education before doing a variety of things: teach writing at the New School, work in advertising, and edit the journal for the American Bar Association among them.

The Omnibus

His foundational works, those included in the Omnibus, were produced during a three-year period of manic productivity. That behind him, he “disappeared from literary life” with such abrupt, mysterious silence that his dropping out was “rather like one of the characters in his books,” as Symons puts it. He apparently later published seven or so works of more tepid fare.

I can’t speak to the later works (can anyone?), though the three in the Omnibus pair well, demonstrating clear consistency in thematic content and execution. The Deadly Percheron (1946) follows respected psychiatrist George Matthews as his treatment of a peculiar patient who claims to work for a leprechaun leads to a world of amnesia, paranoia, and conspiracy. In a neat twist, Matthews briefly resurfaces as a minor character in Bardin’s next, The Last of Philip Banter (1947), which follows alienated businessman Banter as he struggles to make sense of prophetic self-confessions that he doesn’t remember writing. Finally, Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948) is the story of harpsichordist Ellen as she reacclimates to life after being released from an asylum and is confronted by a shadowy figure from her past.

As Symons notes, these are more powerful than perfect novels. He picks out Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly as the strongest of the bunch, and it probably is in terms of pacing and plot, though its prose can be a bit ripe. The Deadly Percheron might be closest to my own taste and slightly less overwrought on the sentence level, though it reflects some odd choices: its plot threads don’t really come together, and the climax is awkwardly shoehorned into an epilogue for some reason.

The Mechanics of Memory and the Metaphysics of the Mundane

In many ways, though, it’s the novels’ zany improvisation that provides their appeal and richness. And they are rich. Here’s a short list of the themes commonly addressed in the Omnibus: mental illness, psychiatry/psychoanalysis, incest, split identities, paranoia, conspiracy, amnesia, the face, mental-health bureaucracy, the hypocrisy and covert barbarism of polite society, and suppressed desires/drives.

That’s a lot, but we could go on. For my money, JFB’s reflections on the mechanics of memory were among his most interesting. In general, he couches those in terms of psychological considerations, but now and then he gives us something like the following from The Deadly Percheron:

Memories exist whole in the mind; to put them down in words demands a sequence, a sense of time and space, of then and now. But when one remembers an event that belongs to the far past and relates it to another happening that belongs to yesterday, these memories exist together simultaneously—they are both, for a moment, now, not then (130).

In places like that, JFB almost suggests Kant in his discussion of time and space as categories of the mind or even Heidegger’s phenomenological account of memory in The Origin of Time (1915) or Being and Time (1927).

Memory is generally the key to cracking the case in a JFB mystery. Hilariously, sleuthing in JFB is often just characters trying to remember who they are or what they have done (“Who was I before I woke up as a guy working in a Coney Island diner?” (Percheron) “Did I write the confessions that appear on my desk?” (Banter) “Am I the person who killed that guy?” (Blue-Tail Fly)).

Memory in Bardin is amenable to diverse readings. A sociologized version might prioritize the repression and dislocation engendered by the consensus culture of postwar American society. A psychological account might underscore the broad complexities of human desire and the impulse toward self-harm.

On my end, I like to read JFB in something of the way I experience Philip K. Dick’s Exegesis: the sincere reflections of a hyperactive mind confronted by inexplicable phenomena in a covertly depraved social context. This is a common theme in PKD’s books, but it was also a central question in his life as he attempted to make sense rationally of irrational experiences such as pink beams of light spontaneously instilling knowledge in his head (or whatever). An experience like that is certainly bound to challenge one’s sense of what exists in the world and how those things exist. Similarly, time and again, JFB has his protagonists confront some bizarre, incongruous phenomenon that kicks off the story: a leprechaun appears to be hiring my patient to distribute horses (Percheron, again), or I appear to have written an unfamiliar confession that accurately reports things that haven’t happened yet (Banter, again).

As scholar Kenneth Payne notes, JFB’s characters are sufficiently self-aware to know that they’re crazy and thus to want the comfort of being told that they’re crazy. If there’s a common implied refrain in JFB, it’s some version of the following from The Deadly Percheron: “I am nuts, thank God! It isn’t really happening!”